Bull worship and sacrifice in Indus valley civilization

Bull sacrifice in Indus civilization

Abstract

The bull sacrifice was a significant issue to the IVC religion and culture. Bull worship was widespread throughout the Mediterranean bronze age cultures, and IVC followed the same practice. Indus seals show the bull figure as a central image around which the inscriptions revolve around. Details are as discussed below.

Picture courtesy – Wikipedia (1)

The above-given picture shows the bullheads excavated from Catalhoyuk in the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara. Catalhuyuk is the oldest civilization, evidenced by archaeological evidence belonging to 8000 BC. The archaeologists have not given any clear idea of why these bullheads were preserved. I think those bulls were sacrificed, and bullheads were placed in the burial room to show the god of death; a bull sacrifice had been made in honour of him, so that deceased would be treated favourably at the time of judgement. I have the feeling; the same was the religious idea of the IVC people and their motive behind the bull sacrifice.

The worship of the Sacred Bull throughout the ancient world is most familiar in the Western world in the biblical episode of the idol of the Golden Calf. After being made by the Hebrew people in the wilderness of Sinai, the Golden Calf was rejected and destroyed by Moses (Book of Exodus). Marduk was the "bull of Utu". Shiva’s steed is Nandi, the Bull. The sacred bull survives in the constellation Taurus, whether lunar in Mesopotamia or solar India; the bulls are the subject of various other cultural and religious incarnations (1).

The Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh depicts the killing by Gilgamesh and Enkidu of the Bull of Heaven, Gugalanna, the first husband of Ereshkigal, as an act of defiance of the gods. The bull was a moon symbol in Mesopotamia (its horns represent the crescent moon) (2 p. 102).

In Egypt, the bull was worshipped as Apis, the embodiment of Ptah and later of Osiris. The Egyptian priests identified the holy Apis bulls after a long series of rituals, and the bulls were housed in the temple for their lifetime, then embalmed and encased in a giant sarcophagus. Bulls were a central theme in the Minoan civilization, with bullheads and bullhorns used as symbols in the Knossos palace. Minoan frescos and ceramics depict bull-leaping, in which participants of both sexes vaulted over bulls by grasping their horns (1).

Bull Figure: Auriga-Aldebaran constellations combined

The bull figure in the Indus seal is the most discussed subject under the topic ‘Unicorn’, but no proper meaning has been attributed. Benght Hemtun says that the bull symbol indicates the Taurus constellation and the horns of the unicorn point towards the star Aldebaran (3). The picture of the bull in the seal coincides with the star constellation.

The narration on the topic "origin of constellations" starts with the remark that the cave paintings at Lascaux in southern France could have been the earliest known sky map depicting the Taurus constellation (The bull figure in the painting). The Pleiades constellation (six stars cluster) is also represented by way of six dots near the bullhead. The International Astronomical Union website has an interesting observation on this Taurus constellation.

The painting is 17,300 years old, showing that the study of constellations started 10,000 years before the emergence of farmers in Anatolia. The man was at the hunting stage of civilization (20,000 BC). (4)

The Indus people used the bullhorn as a pointer; hence, they could have depicted only a single horn instead of the double horn. There is a possibility that Harappan priests were well aware that there were no unicorns at that time, and the unicorn is deliberately drawn to show the subsequent generation it was symbolism, not an actual animal.

Nandi is the bull’s name, which serves as the mount (Sanskrit: Vahana) of the god Shiva and as the gatekeeper of Shiva and Parvati. Temples are venerating Shiva display stone images of a seated Nandi, generally facing the main shrine. There are also some temples dedicated solely to Nandi (5).

The application of the name Nandi to the bull (Sanskrit: vṛṣabha) is, in fact, a development of recent centuries, as Gouriswar Bhattacharya has documented in an illustrated article entitled "Nandin and Vṛṣabha". (6 pp. 1543-1567) The name Nandi was earlier widely used for the bull instead of an anthropomorphic deity who was one of Shiva’s two doorkeepers (7), the other being Mahākāla. Images of Mahākāla and Nandi frequently flank the doorways of pre-tenth-century North Indian temples, and it is in this role of Shiva’s watchman that Nandi figures in Kālidāsa’s poem the Kumārasambhava (5).

The above-given Indus seal shows the god with a horn and tail. The question is, is it indicating Nandi (The doorkeeper) or the God Kalan himself? Bhattacharya thinks both were doorkeepers. I believe that Mahakala was the god of the Dravidian people and had been relegated to the background by introducing Middle Eastern gods (Later Sumerian gods), especially Shiva, suppressing the Kalan but did not exterminate him. Fortunately, Hindu gods are generous; they only suppress some gods but do not eliminate them, unlike modern-day religious zealots.

In conclusion, Mahakala was the death god of Dravidians and was allowed to survive as a doorkeeper to Shiva. The god depicted in the above-given seal is Mahakala himself, not Nandi. Bhattacharya says that Nandi was the gatekeeper. I think Nandi was a kind of doorkeeper and the messenger who conveyed the prayers of supplicants to the God Mahakala. The Aryan god Agni acted as the Purohita and carried the offerings to the gods in the sky. Similarly, Nandi could have worked as the gatekeeper and the messenger.

I have already given a detailed analysis of the messenger god of the Indus civilization in a separate article. Please read the article,’ Leaf messenger symbolism’, for more information on the messenger god. The extract of the said article is reproduced down below for ready reference. (8)

The leaf-messenger

The above-given figure indicates a god or man carrying a stick in a walking position and is also in a leaf shape. It could be a god or an ordinary man. All the Indus seal inscription symbols can be easily interpreted with Vedic rituals mentioned in Grihya-Sutra. Reading Grihya-Sutra indicates that the Vedic people used such a messenger to convey their sacrifice to gods or Pithrus (Manes).

Tammuz was a messenger god

At this stage, it is vital to recollect that ‘"Tammuz’" was a kind of messenger god similar to the role of the leaf- messenger. This water carrier symbol is probably a variant of ‘leaf-messenger-symbolism’.

It is pertinent to note that God Tammuz as messenger appears as a messenger god only after the influence of Middle Eastern priests. The idea of the bull being a gatekeeper and the messenger was a much earlier belief of the Dravidian people.

Figure 1: Gaur ravaging a female

Picture courtesy – Book of Gregory Possehl. (9)

An Indus seal excavated at Chanhu-Daro depicts a bison bull about to mate with a human female lying on the ground. It represents the ‘sacred marriage’ between the bull (the sky god) and mother earth, a fundamental part of religion all over West Asia since Neolithic times. The greatest religious festival in Mesopotamia in the third and second millennia BC was the celebration of the ‘sacred marriage’ of Goddess Ishtar (who presided over love and war) and her lover (who represented the spirit of fertility and grain). This ‘sacred marriage’ involved the partner’s death, lamented by the festival participants (10).

What is the reason for the above-said description of the lover’s death? It looks like the bull was the husband of Inanna and Ereshkigal. However, he was also the messenger to these goddesses. The problem with the messenger’s role is that he had to carry the prayer from the worshipper on earth to the goddess in heaven. In that process, he has to die. The living messenger (i.e. the bull) on the planet, how will it reach heaven with an urgent message? The only way is that the bull (the messenger) has to die. In other words, he was to be sacrificed so that the message could reach the gods. Hence the death of the bull by sacrifice is the essential ingredient of this bull worship.

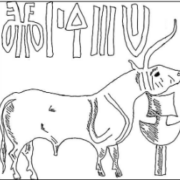

My entire research work on this Harappan seal decipherment revolves around this concept. The bull’s sacrifice has not been illustrated in any seal except for one seal. The seal is reproduced below for ready reference. It looks like the Indus civilization people were highly civilized. Hence they have not crudely depicted the sacrificial ritual.

Picture courtesy – Harappa.com

The above-given seal shows a bull sacrifice scene. But, that is also not a clear-cut illustration; many animals surround the slaughtered animal giving a feeling of a magical situation to the sacrifice performance. Few other seals show the scene of a bull tied to particular trees and sacrificial states. The act of sacrifice has to be only inferred, not openly said.

Why is the bull tied in a ritual way? The only explanation is that the bull was going to be sacrificed. I conclude that bull sacrifice was central to the Indus civilization religion, and all the seals show the sacrifice made. The Indus seals are tokens of evidence prepared for the sacrifice so that the gods in the other world will be pleased when the dead man’s soul reaches before them for judgement.

The second explanation for the bull depiction is that the bull figure showed the direction from which the inscription should be read. Reading of the inscription should start from the side faced by the bull. This was the methodology used by the Egyptian scribes. Read my article,‘ Indus script follows Egyptian hieroglyphic way of writing’, for more information on this issue. (11)

Figure 2: Three bulls tied to three different trees.

Picture courtesy – Book of Asko Parpola. (12 p. 21)

Picture after – (13)

Asko Parpola sees a connection between the cultic object in front of the Indus "unicorn" and the three bulls tied to three different trees in the painted pottery of the Kulli culture of southern Baluchistan. In the Kulli pottery, a humped bull is tethered to this object. In contrast, in the painted pottery of Nausharo, dated to the transitional period between the Early and Mature Harappan phases (c. 2600-2500 BC), the zebu bulls are tethered to different trees. Asko Parpola suggests that the cultic object before the "unicorn" represent some sacrificial stake. Vedic animal sacrifices also express a similar idea: the bull must be tied to a yūpa before the sacrifice (10).

Figure : The Harappan seal depiction shows that the sacrificial bull is tied to a specific tree

It is more or less certain that the ritual object before the bull is a dhoop stand. Read my article,‘ Incense burner and Indus seal,’ for more information. Asko Parpola, in his book, observes that this object may be a sacrificial stake (14). He states that initially, the Bulls were tied before specific trees, where the village spirits resided; later, it was reduced to stakes made of that particular tree. It looks like the stakes also got transformed into a dhoop stand. This sacrificial stake is an evolutionary process; we see the last stage of development in the seal.

All these above discussions show that the bull was worshipped in Indus Valley. I saw the worship and adoration of the temple bull in my village 40 years back. Unfortunately, the temple bull has vanished in my village as of today. All these cultural activities are fast disappearing, and after some time, the younger generation will not be able to make any sense of the cultural beliefs of villagers.

Such a situation already exists; that is why we cannot decipher the Indus script. We cannot comprehend the simple idea of bull sacrifice, which happened in the Indus civilization because of the long period involved. Further, there were changes in religious beliefs and practices. Because of the said reasons, we cannot visualize the bull sacrifice idea of the Indus Valley people.

There is a difference between the temple bull and other ordinary bulls illustrated in the Indus seals. The temple bulls were not sacrificed; they were allowed to age and die naturally. But the Bulls depicted in the Indus seals were sacrificed. That is the central theme of my research work and has been elaborated under various articles in my research work.

‘Ningishzida’, the Sumerian dragon in the Indus Valley civilization

Figure 4: Indus God with projections on his shoulder.

See the above-given figure-4; the symbol of a god with projection on shoulders also appears in Indus seal inscriptions. No such god appears in modern-day Hinduism. However, such a god existed in Sumerian civilization; he was called ‘Ningishzida.’ This evidence shows the link between ancient Sumeria and Indus Valley Civilisation.

In Sumerian mythology, Ningishzida appears in Adapa’s myth as one of the two guardians of Anu’s celestial palace alongside Dumuzi. He was sometimes depicted as a serpent with a human head. (15)

Ningishzida was introducing king Gudea to God Enki.

Picture acknowledgements: (16)

The above-given picture is a drawing (1992) from Gudaea’s cylinder seal showing King Gudea of Lagash, Ningishzida and a seated god identified as Enki according to Black and Green (16) (17 p. 139).

Nin-gish-zida (Gishzida) can be identified with "serpent-dragon" heads erupting from his shoulders. The figure indicates that he can alternately assume the form of a walking, four-legged, winged and horned dragon. He presents a human petitioner, King Gudaea of Lagash in ancient Sumer, to a seated god holding a vase of flowing waters, "the water of life" (seated on a throne of flowing waters). This god may be Enki (Ea), the Sumerian god of Wisdom and Knowledge (Akkadian: Ea), whose main temple was at Eridu. (16)

Figure 5: Ningishzida in human form as well as in dragon form.

Picture acknowledgements: (16)

The above-given drawing (1928) from a cylinder seal of King Gudea of Lagash, ca. 2100 BC, shows Ningishzida as a human with serpent-dragon heads erupting from shoulders. His other animal form is a dragon four with horns and wings at the lower left corner of the above-given picture (18 p. 57) (16).

Figure 6: Indus Valley ‘Ningishzida.’

Picture courtesy: (19)

The relevance of this above-given discussion is that the same ‘dragon’ also appears in Indus Valley seals. See the above given Harappan seal figure; it has all characteristics of ‘Ningishzida‘ of Sumerian civilization. The only difference is that a bull’s expression dominates the Indian Ningishzida.

Instead of verifying the parallelism available in nearby civilizations, Indian archaeologists believe in the ‘Local Origin theory’ and try to develop entirely new ideas which cannot be verified. This approach is one of the reasons for the Indus script remains undeciphered so far.

Ningishzida was a mediator god who introduced the dead person before the god of death for a favourable judgement. And this idea lingers on as on today in the form of bull worship—i.e. ‘Nandi’, the vahan of God Shiva. It looks like the bull played such a role in the Indus civilization.

Ningishzida had ‘double roles’ like some heroes in movies. His first form is the animal form, the ‘dragon’, and his second form is a human form with dragons projecting out of his shoulders. Further to explain this point, he could transform himself into a human shape and was able to talk. This capacity of transformation was given to him to present the case of a dead man before god.

The other possibility is that the dragon form of Ningishzida seems to be the ‘Vahan’ (Vehicle) of the god. In Hindu mythology, all gods can be easily identified by their respective‘ Vahans‘. In contrast, Western Scholars are unaware of this concept and may conclude that the dragon is the ‘double’ of the god. In reality, the dragon may be only the vahan of the god.

Clearly, the Sumerian civilization had influenced the Indus valley civilization. Following up the Sumerian religious idea in the Indus valley civilization context will immensely benefit the decipherment of Indus valley seal inscriptions.

Picture courtesy- Wikipedia (20) (21)

Lamassu

In art, Lamassu were depicted as hybrids, either winged bulls or lions with the head of a human male. The motif of a winged animal with a human head is common to the Near East, first recorded in Ebla (Sumeria) around 3000 BCE (22) (23).

Assyrian sculpture typically placed prominent pairs of Lamassu at entrances in palaces, facing the street and internal courtyards. They sometimes appear within narrative reliefs, apparently protecting the Assyrians.

The Lammasu or Lumasi represent the zodiacs, parent stars, or constellations (24 p. 85). They are depicted as protective deities because they encompass all life within them. In the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh, they are represented as physical gods, where the Lammasu iconography originates. Although "lamassu" had a different iconography and portrayal in Sumerian culture, the terms lamassu, alad, and shedu evolved throughout the Assyro-Akkadian culture from the Sumerian civilization to denote the Assyrian-winged-man-bull symbol and statues during the Neo-Assyrian Empire (25).

Lamassus appear as the gatekeeper at Louvre Museum.

Picture courtesy – Wikipedia. (20)

The above-given narration gives a view that Lamassu were gatekeepers as well as protective deities. Only the messenger role is missing. All these analyses show that Lamassu is similar to Ningishzida bulls shown in the IVC seals. But they have wings like the Sumerian Dragan Ningishzida and Human heads like Indus Valley seal Ningishzida, whereas the bull with eight different animal composite has a human face. It looks like he was not merely a gatekeeper but also a demigod and messenger to god. Most probably, he was sacrificed to convey the prayers to the gods in heaven.

Figure : Dhoop stand.

Picture courtesy – Puneet Gupta (26)

Now, we should devote some space and time to the other symbol appearing in these seals, along with the bull. There is a ritual vessel depicted in front of the bull. What could be the role of this vessel?

The object before the animal is variously described by different people. Mahadevan says that it looks like a filter and most probably was a kind of filter used for soma juice, but he points out the contradiction that Soma is known to latter-day supposed to be Indo-Europeans and not Indus people. (27)

I think it is a ‘Dhoop stand’ (Incense burner) used in temples. I had seen such an incense burner in the Cochin museum; unfortunately, I could not get a photograph. Fortunately, such a dhoop stand figure is available in the video Puneet Gupta presented on YouTube (26). The video shows that the object placed before the bull is a dhoop stand. Puneet Gupta is also an IVC enthusiast and confirms that the object is a dhoop stand.

1. wikipedia(Sacred_bull). Sacred_bull. wikipedia.org. [Online] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_bull.

2. Cashford, Jules. The Moon: Myth and Image. 2003.

3. Hemtun, Bengt. Indus Symbols. www.catshaman.com. [Online] April 8, 2008. [Cited: March 3, 2009.]

4. The pleiades in the "Salle des Taureaux" Grotte de Lascaux (France). Rappengluck. 1996, Proceedings of the IV th SEAC meeting "Astronomy and culture", pp. 217-225.

5. wikipedia(Nandi-bull). Nandi_(bull). wikipedia. [Online] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nandi_(bull).

6. Bhattacharya, Gouriswar. "Nandin and Vṛṣabha". Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft, Supplement III,2, XIX. Deutscher Orientalistentag, . 1977.

7. jeyakumar(Gate-keeper-god). Karuppa_Swami_was_the_gate_keeper_god. academia.edu. [Online] 2015. https://www.academia.edu/10950376/Karuppa_Swami_was_the_gate_keeper_god.

8. Jeyakumar(Leaf-messenger). Leaf-messenger_symbolism. academia.edu. [Online] 2015. https://www.academia.edu/19742902/Leaf-messenger_symbolism.

9. Possehl.G.L. The Indus Civilization A Contemporary Perspective. New Delhi : Vistaar Publications, 2003.

10. Zutshi, Vikram. asko-parpola-on-the-roots-of-hinduism-by-vikram-zutshi. www.sutrajournal.com. [Online] 2016. http://www.sutrajournal.com/asko-parpola-on-the-roots-of-hinduism-by-vikram-zutshi.

11. Jeyakumar(hieroglyphics-link). Indus symbols follow the Egyptian hieroglyphics way of writing and ideas. Academia.edu. [Online] 2021. https://www.academia.edu/43722883/Indus_symbols_follow_the_Egyptian_hieroglyphics_way_of_writing_and_ideas.

12. Parpola, Asko. Deciphering the Indus script. New York : Cambridge University Press, 2000.

13. excavations at Nausharo. Jarrige. 1987-88, PA3, pp. 149-203.

14. Parpola, Asko. The roots of Hinduism: The early Aryans and Indus civilization. s.l. : Oxford publishers, 2015.

15. Wikipedia(Ningishzida). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ningishzida. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ningishzida. [Online] july 2015. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ningishzida.

16. Reinhold, Walter. Serpentningishzida.html. http://www.bibleorigins.net. [Online] 2015. http://www.bibleorigins.net/Serpentningishzida.html.

17. Black, Jeremy and Green, Anthony. Gods , Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia,An Illustrated Dictionary. Austin, Texas : University of Texas Press, 1992.

18. Wooley, Charles Leonald. The Sumerians. Oxford : Clarendon Publisher., 1929.

19. Sullivan, Sue. The Indus script dictionary. s.l. : Suzanne Redalia (Publisher), 2011.

20. Wikipedia(Lamassu). Lamassu. wikipedia.org/wiki/. [Online] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lamassu#cite_ref-12.

21. wikipedia(Uni.Chi.Ori.Ins). University_of_Chicago_Oriental_Institute. en.wikipedia.org/wiki. [Online] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/University_of_Chicago_Oriental_Institute.

22. BBC. history/ancient/cultures/mesopotamia_gallery_. /www.bbc.co.uk. [Online] http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/cultures/mesopotamia_gallery_09.shtml.

23. ancientneareast.net. mesopotamian-religion/lamassu/. ancientneareast.net. [Online] http://www.ancientneareast.net/mesopotamian-religion/lamassu/.

24. Hewitt, J.F. History and Chronology of the Myth-Making Age. .

25. livius.org/. mythology/lamassu-bull-man. http://www.livius.org. [Online] http://www.livius.org/articles/mythology/lamassu-bull-man/?.

26. Gupta, Puneet. Dhoop stand. youtube.com. [Online] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iMB7y57sJJY&list=LLPDkxkai5ltXZkEQbZujwRA&index=4.

27. Jeyakumar(Insense-burner). Incense burner and Indus seal inscriptions. Academia.edu. [Online] 2019. https://www.academia.edu/42077733/The_incense_burner_and_Indus_seal_inscriptions.