Cone symbol means ‘given eternal life.’

Abstract

The cone symbol intrigued me for a long time; finally, a beautiful meaning has emerged. This cone symbol indicates the act of ‘ giving eternal life’ by Egyptian god Heh. Other gods also vied for the same power. God Heh gave the mortals eternal life of million years, and he got transformed into ‘God Ayyappa’ in the Indian context.

Figure 1: Triangle – Indus symbol.

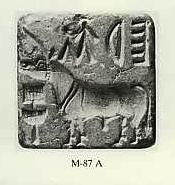

Figure 2: Indus seal showing the conical object.

Seal picture courtesy – (1)

Figure 3: Photo shows the conical object in Vedic ceremony.

Picture courtesy – (2)

Cone object in the ritual ceremony

The above-given photo shows a traditional Hindu marriage, and Vedic Yajna is being performed. Note the conical shaped object in the right-side bottom corner of the photograph. (2) The relevance of this conical object to the Indus Valley Civilization symbol is that a similar conical symbol appears in the Indus script. Most probably, the cone indicates the presence of God Sah/Sahu (Egyptian god). I made inquiries with many priests regarding the ‘cone object’ meaning in a yajna ceremony. The priests are aware of this conical object but do not know the meaning or significance of using that conical object. The importance of a vital ritual is forgotten, but only the remnant of the tradition is still being practised.

Figure 4: Grave goods – conical bread made of clay

Picture courtesy – Flicker.com

Ancient Egyptian Funerary Cones were part of grave goods

Funerary cones are a type of funereal object from ancient Egypt. It is well known that the ancient Egyptians were highly concerned about the afterlife and did all they could to provide for the dead. Funerary goods were buried with the dead to provide protection and sustenance in the afterlife (3).

Amulets and magic spells, for example, protected and aided the dead in their journey through the underworld, whilst little figurines called shabtis could be magically animated to perform tasks for the dead in the afterlife (3).

Making Funerary Cones

Funerary cones are made of fired Nile mud and are most commonly found to be conical, hence its name. Nevertheless, there are also funerary cones of other shapes, though these are understandably less common. Other shapes include pyramidal, horn-shaped, trumpet-shapes, double-headed and triple-headed cones (only one example of each is known at present), as well as cone-imitated bricks (3). Similar is the case of Indus script symbols. The cone symbol appears in different types. Below given are some examples.

There is a possibility that the rhino horn could have been used instead of the ‘clay cone’ in the Indus civilization context. The rhino horn could have been an excellent material to inscribe on it. However, it would not have survived the ravages of time. Both ‘clay cones and rhino horns’ have not been found in excavations of Indus sites.

Figure 5: The picture shows the triangle formed by three prominent stars.

Winter Triangle

The Winter Triangle, or the Great Southern Triangle, is an asterism formed by three bright stars in three prominent winter constellations. These stars are Betelgeuse in Orion, Procyon in Canis Minor and Sirius in Canis Major constellation and it is prominent in the night sky in the northern hemisphere during the winter months, from December to March. This could be the idea behind the identification of the god Sothis with this triangle symbol.

Egyptian funerary cones of Mentuemhet with hieroglyphics- 650 BC…

Picture courtesy Ancient origins.net (3)

The inscriptions on funerary cones indicate the name of its owner (usually an official serving a pharaoh) and his title. These are stamped onto the face of the cone, which has an average diameter of between 5-10 cm (2-4 inches) (3).

Purpose of Funerary Cones

It is unclear what the funerary cones were used for, and various hypotheses have been put forward over the years. Some, such as Champollion, suggest that the cones served as some sort of labels for the deceased. (3)

Researcher Petrie is of the opinion that the cones were symbolic offerings. Others researchers speculate that the cones were architectural ornaments, architectural material to reinforce the entrance wall, solar symbols, and even phallic symbols. No one knows for certain what the cones were used for, but they were obviously important to death rituals for some time. (3)

Figure 6: Clay cone of Gudea of Sumeria.

Picture courtesy- Wikipedia-commons (4)

Cone symbol in ancient Sumeria

The above-given picture shows the Mesopotamian cuneiform foundation cone, not a religious offering of conical bread as in Egypt. (Neo-Sumerian period, 2120 BC). This cone was dedicated by Gudea, the governor of Lagash, to the god Ningirsu, the mighty warrior of Enlil, to construct the Eninnu Temple. Cuneiform inscriptions cover the entire surface area of the cone. The size of the cone is 4.75 x 2.5 inches.

The objective of cone object in Sumeria as well as in Egypt is looking similar. In both cases, the individual’s name and designation are mentioned. And also, the name of the god to whom the offering/dedication is made is also mentioned. The objective seems to be that the person’s name and meritorious work should be put forth before the god and produced as a permanent record to give the dead man’s soul favourable treatment at the netherworld.

Figure 7: Bread cone and Sothis cone

Picture courtesy – Barry Carter (5)

The “white bread” cones are often adjacent to a hieroglyph that is called the “Sacred Sothic Triangle” (6). The above-given picture shows the difference between conical bread and the Sothis triangle. The Sothis triangles seem to be more regular in shape than the bread cones (5).

The above-given picture shows another critical character of this Sothis triangle (5). This triangle always appears in pair form along with the ankh symbol. This pair of symbols give a meaning ‘given everlasting life.’ In the Indus script also the cone symbol is always followed by the branch symbol. Brach symbol means ‘sastha (god). (7) This pairing of these two symbols shows that, as such, it was the name of a god, not merely shewbread.

Sah and Sopdet – Father and mother of Egyptian gods

In Egyptian mythology, Sah was the “Father of the gods”. The above-given picture of Sah is the anthropomorphic representation of a prominent Egyptian constellation represented by the modern constellations of Orion and Lepus. (8) (9) This representation also includes stars from modern Eridanus, Monoceros and Columba constellations. (10) His consort was Sopdet (Spdt), known by the ancient Greek name as Sothis, the goddess of the star Sirius (the “Dogstar”). Sah became associated with a more important deity, Osiris, and Sopdet with Osiris’s consort Isis. (11 p. 129)

Sah was frequently mentioned as “the Father of Gods” in the Old Kingdom Pyramid texts. Pharaoh was thought to travel to Orion after his death. (11) This above said observation of Wilkinson and Richard seems to be important. The entire scheme of mortuary temples and rituals are oriented towards the afterlife journey of a dead man’s soul. The soul’s final destination is the Orion constellation, which is the world of the God Sah, the ancient father.

In the context of Hindu religious ideas, this Egyptian god could have been replaced by Brahma and Brahma-Loka because Brahma was the first god who emerged of his own in this universe at the time of the creation of gods and animals. Brahma only created all the other gods and beings; he was also the father of all other Rishis. Hence, Brahma looks similar to the father god of Egyptian gods.

Figure 8: Goddess Sopdet

Picture courtesy -Wikipedia

During the early period of Egyptian civilization, the heliacal rising of the bright Sothis star preceded the usual annual flooding of the Nile (11). Therefore, it was used for the solar civil calendar, which largely superseded the original lunar calendar in the 3rd millennium BC. Despite the wandering nature of the Egyptian calendar, the erratic timing of the flood from year to year, and the slow procession of Sirius within the solar year, Sopdet continued to remain central to cultural depictions of the year and the Egyptian New Year. She was also revered as a goddess of fertility brought to the soil by the flooding. (12)

During the Old Kingdom, she was an important goddess of the annual flood and a psychopomp guiding deceased pharaohs through the Egyptian underworld. During the Middle Kingdom, she was primarily a mother and nurse and, by the Ptolemaic period, she was almost entirely subsumed into Isis. (11)

Figure 9: Hieroglyphic symbol of Sopdet (Sothis)

One important thing to be noted here is the hieroglyphic name of Sopdet. See the conical symbol glyph is appearing in the name of the god. Literally also, the word ‘Sopdet’ means “Triangle” or “Sharp One”. There is a possibility that the conical symbol could be indicating the goddess Sopdet (Greek name Sothis). (Or) The other possibility is that the cone symbol could mean the god Sah, who was also called Sahu.

One relevant observation to be noted here is that both these names are appearing as name titles even today in India. The title ‘Sah’ is common in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. The title ‘Shah’ (sounds like ‘Sah’) is common in Gujarat. The title ‘Sahu’ is prevalent in the state of Orissa.

God Dakshinamurthi.

Picture courtesy –Wikipedia (13)

‘Proto- Shiva’ seal and Dakshinamurthi

The above-given picture shows the god Dakshinamurthi, surrounded by sages. This god is generally shown with four arms. He is seated under a banyan tree, facing the south. He is sitting upon a deer throne and surrounded by sages who are receiving his instruction. In many other depictions, this god is surrounded by wild animals instead of sages.

Figure 10: Sky map showing Orion constellation

Picture courtesy – Wikipedia

Further, the southern side position of Dakshinamurthi is reaffirmed by the position of the Orion constellation in the southern hemisphere of the sky. The Orion constellation is located south of the ecliptical pathway, Sun, moon, and other planets’ pathway. The basic visualization of Hindu priests is that all the celestial gods (Planets) pass through a pathway (ecliptic pathway), which is also the central axis of the Hindu temple. In this scheme, Orion is a minor god on the southern sidewall of the Garbha Graha (Inner Sanctorum of the temple). Finally, the name ‘Dakshinamurthi’ literally means ‘god of the southern side.’

The relevance of this discussion about Dakshinamurthi is that the ‘Proto-Shiva’ seal corresponds with this god Dakshinamurthi in all aspects. For more details, read my article,” Proto-Shiva seal and Dakshinamurthi”. (14)

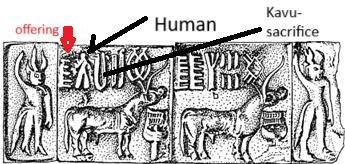

Indus seal showing ‘Proto-Shiva’/ Brahma/Dakshinamurthi

Orion constellation and surrounding animals

The conclusion is that the god depicted in the above-given seal could be Sah/Sahu of the Egyptian god. We do not know what the name by which Indus people called this god is. Till a finality is arrived at on this issue, we shall call him ‘Mrigasira’ (god surrounded by animals).

The conclusion is that the Egyptian god Sah is associated with the Orion constellation and is called ‘Dakshinamurthi’ by modern Hindu priests. The Canis Major constellation was viewed as Goddess Sopdet (Sothis in Greek) by ancient Egyptian people, but it is unclear how the Indus people called this god. This Canis Major is shown as ‘Tiger’ in Indus seals.

Finally, what is the meaning of the cone symbol?

Cone symbol stands for the god ‘Sah/Sopdet’ and the concept of the final salvation of a soul. The Cone symbol also stands for the word ‘Given’ as interpreted by Egyptologists.

The researcher Max Distro states that the ancient Egyptian Bread Cone is one of the oldest ideas from Ancient Egypt. It was used in the early dynasties of Egypt. Max Distro explains that the meaning of the Bread Cone is: “to give”, “present”. The above given hieroglyphic inscription says that the pharaoh was “Given Eternal life like Ra”. (15)

Similar is the situation of interpreting the ‘cone’ symbol of Indus script. It does not merely indicate the offering of conical bread to god. It does not simply mean the god ‘Sah/Sopdet’. This cone symbol indicates the broad idea of giving eternal life to the soul of a dead person. It looks like the final funeral ceremony in which the soul entered the netherworld at Orion constellation, and the soul was given eternal life to live with ‘Sah’.

Frequency distribution analysis

The research paper submitted by Sundar et al. contains the statistical analysis and frequency distribution analysis of various Indus symbols (16). The data about cone symbol are extracted and presented in the below-given table.

Table 1: frequency distribution analysis table by Sundar et al.

|

Symbol

|

Solus

|

Initial

|

Medial

|

Final

|

Total

|

|

|

0

|

29

|

2

|

0

|

31

|

|

|

0

|

15

|

0

|

0

|

15

|

|

|

0

|

12

|

0

|

0

|

12

|

|

|

0

|

0

|

15

|

1

|

16

|

|

|

1

|

5

|

6

|

0

|

12

|

|

|

0

|

5

|

6

|

0

|

11

|

|

1

|

66

|

29

|

1

|

97

|

|

Symbol

|

total

|

Reading of symbols

All these pairs of symbols should be read from right to left

|

Meaning

|

|

|

31

|

Eternal life and Gatekeeper god

|

The meaningful pairing of symbols

|

|

|

15

|

Eternal life – Sastha

|

The meaningful pairing of symbols

|

|

|

12

|

Karma- Eternal life

|

This combination is meaningful because ‘Karma’ceremony is performed for ‘Pithrus’, for obtaining eternal life.

|

|

|

16

|

Eternal life -Kavu (Sacrifice)

|

Meaningful association of symbols

|

|

|

12

|

Eternal life- Kur

|

Kur is the netherworld indicated by three mountains. God Sah was the lord of ‘Kur.’

|

|

|

11

|

Eternal life- seventh day

|

It is a meaningful association and an important one also. It says Sah was the lord of the seventh day.

|

|

97

|

|

|

All the above-given pairs are meaningful. Thanks to the research work of Mahadevan (17) and Sundar (16), all their statistical analysis work of Indus symbols have yielded some excellent results.

God Ayyappan

Finally, it is relevant to mention that the ‘cone’ doesn’t merely indicate Sah and sopdet; it ultimately means their son ‘god Ayyappa’ in the Indian context. Read my article ‘difference between ‘ Ayyappan and Ayyanar’ for more information. (17)

1. Sullivan, Sue. Indus Script Dictionary. s.l. : Suzanne Redalia, 2011.

2. iskconklang. vedic-wedding-for-tulasi-maharani-and-saligram. iskconklang.wordpress.com/. [Online] November 2015. https://iskconklang.wordpress.com/2008/11/27/vedic-wedding-for-tulasi-maharani-and-saligram/.

3. ancient-origins.net. examining-cryptic-grave-goods-what-are-ancient-egyptian-funerary-cones-. https://www.ancient-origins.net. [Online] 7 February 2016. https://www.ancient-origins.net/artifacts-other-artifacts/examining-cryptic-grave-goods-what-are-ancient-egyptian-funerary-cones-020736.

4. commons.wikimedia.org. Sumerian_-_Gudea_Cone_-_Walters. [Online] https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sumerian_-_Gudea_Cone_-_Walters_481461_-_View_A.jpg.

5. Carter, Barry. shewbread. subtleenergies.com. [Online] http://www.subtleenergies.com/ormus/tw/shewbread.htm.

6. Musaios. “The Lion Path: You Can Take It With You”. s.l. : Golden scepture, 1989.

7. Jeyakumar(Sastha). Branch_symbol_indicates_the_word_Sastha. academia.edu. [Online] 2016. https://www.academia.edu/31658123/Branch_symbol_indicates_the_word_Sastha..

8. wikipedia(Sah). Sah_(god). wikipedia.org. [Online] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sah_(god).

9. “On the Orientation of Ancient Egyptian Temples: (1) Upper Egypt and Lower Nubia”. Shaltout, Belmonte. s.l. : Shaltout, Belmonte (August 1, 2005). “On the Orientation of Ancient Egyptian TempJournal for the History of Astronomy. 36 (3): 273–298. doi:10.1177, 2005. Shaltout, Belmonte (August 1, 2005). “On the Orientation of Ancient Egyptian Temples: (1) Upper 002182860503600302..

10. Belmonte, J.A. Calendars, symbols and orientations: Legacies of astronomy in culture – The Ramesside star clocks and the ancient Egyptian constellations . Stockholm : s.n., 2003.

11. Wilkinson, Richard H. The complete gods and goddesses of ancient Egypt. London : Thames & Hudson. , 2003. ISBN 978-0-500-05120-7..

12. wikipedia(Sopdet). Sopdet#CITEREFVygus2015. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sopdet. [Online] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sopdet#CITEREFVygus2015.

13. wikipedia(Dakshinamurthi). Dakshinamurthy. wikipedia. [Online] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dakshinamurthy.

14. Jeyakumar(Dakshinamurthi). https://www.academia.edu/31640723/Proto-Shiva_seal_and_Dakshinamurthi. Academia.edu. [Online] 2017. https://www.academia.edu/31640723/Proto-Shiva_seal_and_Dakshinamurthi.

15. Distro, Max. egyptian-hieroglyphs-and-sacred-symbols. traveltoeat.com. [Online] https://traveltoeat.com/egyptian-hieroglyphs-and-sacred-symbols/.

16. Sundar, G.,Chandrsekar,S.SureshBabu,G.C.,Mahaadevan,I. The-Indus-Script-Text-and-Context. wordpress/wp-content/uploads. [Online] 2010. http://203.124.120.60/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/43-The-Indus-Script-Text-and-Context.pdf.

17. Jeyakumar(Ayyappan). https://www.academia.edu/31640471/Difference_between_Ayyappan_and_Ayyanar. https://www.academia.edu/31640471/Difference_between_Ayyappan_and_Ayyanar. [Online] 2018. https://www.academia.edu/31640471/Difference_between_Ayyappan_and_Ayyanar.

indicates god, which needs verification.

” symbol indicates the word “kavu”, which conforms to IVC scripts. Read my article, “Kavu Symbol Indicates Sacrifice in Indus Inscriptions,” for more information. (4)