Necropolis theory on Indus Valley civilization

Abstract

Mohenjo Daro means, “It was the mound of the dead,” and the word itself is self-explanatory. The view that nearly 50,000 people lived at its demise is not an acceptable theory because such a crowded condition would have resulted in diseases. It is likely, Indus people built mortuary houses and temples on these sites, and these clustered mortuary houses give the impression of a city.

The structure identified as a granary is doubtful; the photographs on the website Harappa.com show that it looks more like a brick kiln than a granary. Storing grains on such a large scale is difficult; grains will rot, and insects and rats will attack. Based on these factors, I concluded that the structure was not granary but could be a brick kiln.

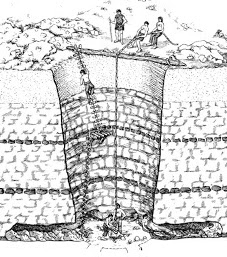

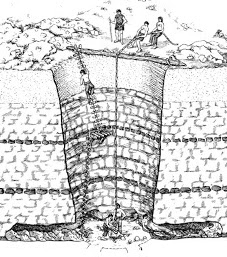

The photo of the blocked drain presented on the same website shows that it could be merely an entrance to a tomb. A photograph of the well indicates that it could be a tunnel (Shaft Grave) to the inner burial chamber at a lower level, but it looks like a well. The “toilets” described by archaeologists seem to be “ordinary holes” meant for pouring sacrificial blood into underground burial chambers. The potteries also look like that, as if they have been tailor-made to the needs of funeral practices. Some show a protruding tube for funnelling the sacrificial blood into the ground.

Keywords:

Blocked drain, Blood sacrifice, Brick kiln, Burial chambers, Funeral practices, Granary, Harappa, Indus Valley Civilization, Mohenjo Daro, Necropolis, Tomb, and Toilets

Necropolis theory on Indus civilization

Mohenjo Daro means, “It was the mound of the dead,” and the word itself is self-explanatory. Even in Medieval times, it is likely that these sites could have been used as burial places; an Islamic tomb at Harappa and a Buddhist stupa at Mohenjo Daro substantiate this proposition. The name ‘Lothal’ also means mound of the dead in the Gujarati language. Indian archaeologists claim that there was a ship dockyard at Lothal. Whereas Lawrence argues that it was merely an irrigation tank, there is no supportive evidence for any shipyard. (1)

I visited many excavation sites in Gujarat; all are called ‘Timbo’ (mound). All sites are deserted and are located one or two kilometres away from nearby villages. This kind of isolation is a typical characteristic of a burial place. In a normal situation, no village will be deserted. The deserted nature of these sites shows that they were haunted places and dwelling places of ghosts.

Nevertheless, archaeologists are going to various lengths to prove otherwise. These excavated sites are necropolises and not metropolises as imagined by various archaeologists. For example, the standard view is that nearly 50,000 people lived in Mohenjo Daro at the prime of its existence. The idea of the metropolis is unacceptable because 50,000 dead bodies could be kept in such a congested condition, but not 50,000 living people. Many people living in unsanitary conditions would have resulted in an outbreak of epidemics and many deaths.

The standard view about Mohenjo-Daro is that it was most likely one of the administrative centres of the Indus Valley Civilization in ancient times. It was the most developed and advanced city in South Asia, perhaps in the world, during its peak existence. The planning and engineering showed the town’s importance to the people of the Indus valley. Now the time has come to reconsider this view.

No such big cities existed at that period in any part of the world. Many people living in big congested cities would have resulted in outbreaks of diseases and death in large numbers. In ancient times, villages did not grow beyond the population of a few thousand because of the threat of epidemics. At the maximum, a town could have withstood a population of 10,000, not more than that. However, the archaeologists estimate that nearly 50,000 to 1,00,000 people would have lived in Mohenjo Daro, and Harappa would have sustained an equal number of people. Such a high population density was impossible then; hence, a proper explanation is needed for the dense construction of houses on these sites. It is likely that only dead bodies were kept in those houses, and people were not living in those sites. This new hypothesis explains the high density of homes found in these sites. The new theory is that these sites were necropolises, not metropolises as popularly imagined so far.

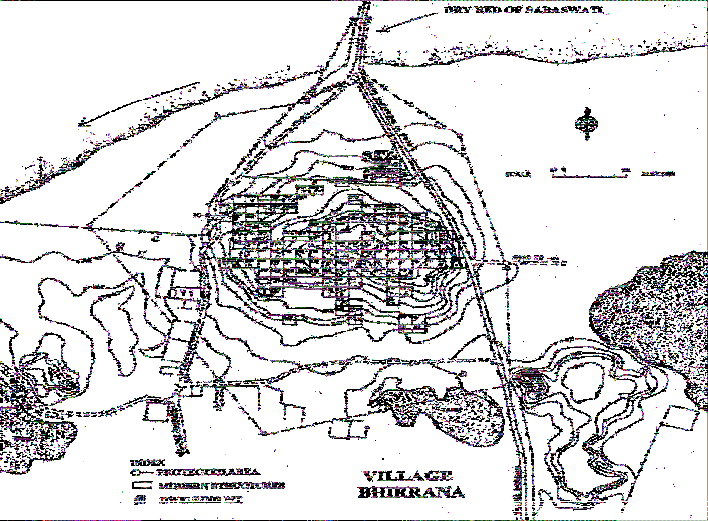

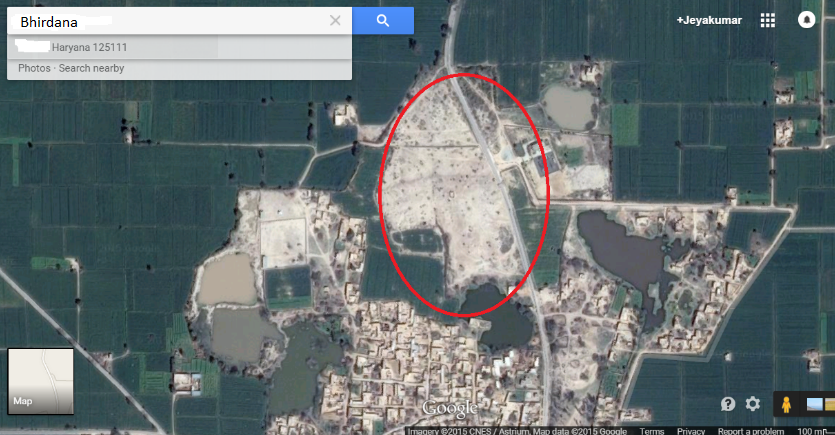

The mystery of Bhirana mound, Haryana

Bhirrana or Birhana (In Google Maps, it is named Bhirdana) is a small village in Fatehabad District in the Indian state of Haryana. According to a December 2014 report by the Archaeological Survey of India, Bhirrana is the oldest Indus Valley Civilization site, dating back to 7570-6200 BCE. (2)

The site is situated about 220 km northwest of New Delhi on the New Delhi-Fazilka national highway and about 14 km northeast of the district headquarters on the Bhuna road in the Fatehabad district. The site is one of the many sites seen along the channels of the ancient Saraswati riverine systems, now represented by the seasonal Ghaggar River, which flows in modern Haryana from Nahan to Sirsa. (2). The mound measures 190 metres north-south and 240 metres east-west and rises to a height of 5.50 metres from the surrounding area of the flat alluvial plain.

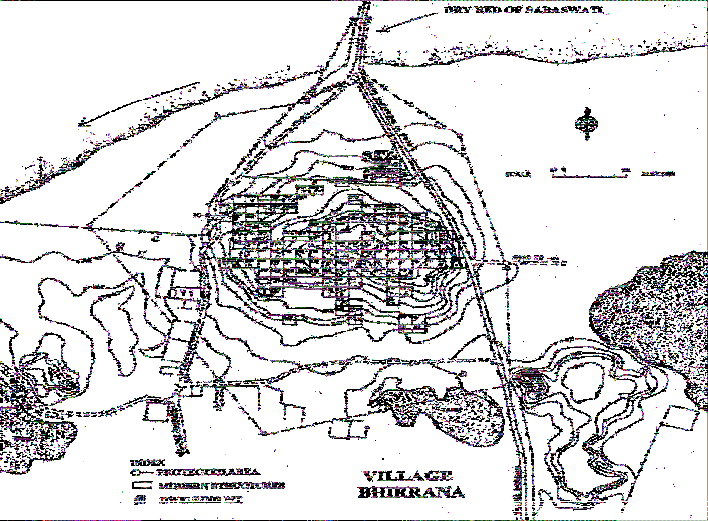

Figure 1: Line map of Bhirhana. Picture courtesy -Narender Parmer (3)

Figure 2: Same area as per the Google map. Picture courtesy (4)

I downloaded the Google map of the excavation site and reproduced the same here as Figure 2. Compare this Google map with a line map (figure-1) by Narender Parmar. (3) See the area on the northern edge of the village (Marked with a red line), which had remained unoccupied for thousands of years, waiting for the archaeologist to excavate. Strange. Why was this area never occupied? People have not deserted the nearby village. Archaeologists claim that Mohenjo Daro was abandoned and Harappa was deserted for various reasons. However, this village is not deserted, but evidence about the period 7000 BC is still available. Why is it so?

Mystery Mounds of Indus Civilization

The mystery is why the mound area alone is not occupied for thousands of years. The same question applies to all excavation sites of the Indus civilization. Indian archaeologist visit some village, finds a mound, and immediately declares that he has found an ancient Indus Valley city. How is it possible? Evidence for any other civilization appears in small numbers, with few excavation sites. Whereas evidence for Indus Valley Civilization appears in thousands, why is it like that? What made all these sites preserved for so many thousands of years? I am not disputing that these sites are thousands of years old; I accept that as a fact. But, my question is, how and why were these sites never re-occupied and remained unoccupied for thousands of years?

Over two thousand sites of the Harappan culture have been discovered so far, of which only half a dozen are cities and slightly more than a dozen can be identified as towns. The rest of the settlements fall into different categories like small or big villages, processing centres, ports, and temporary camps to exploit local natural resources. This data has enabled the reconstruction of the urban life of the Harappan people, but it represents less than 3% of the Harappan population. We have, however, a minimal idea of their rural lifestyle, where more than 97% of Harappans lived. It looks like “Small village Archaeology” does not seem to be a priority of the Harappan archaeologists. (5)

All Indian archaeologists classify these sites in various categories, but none identify them as burial places or necropolises. In reality, all Indus excavated sites are either burial grounds or necropolises. This misidentification has resulted in absolute confusion about the nature of the Indus Valley Civilization.

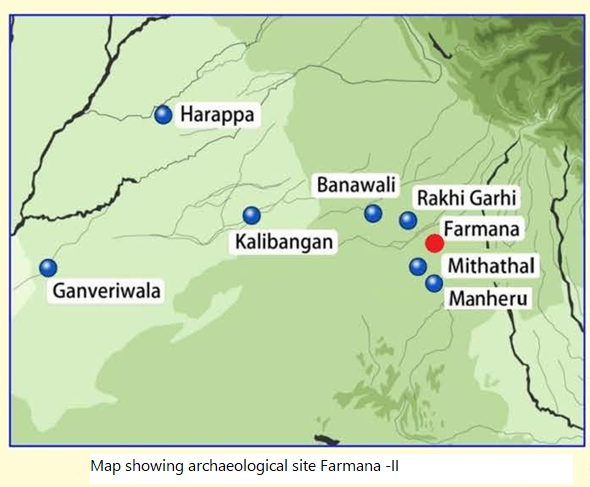

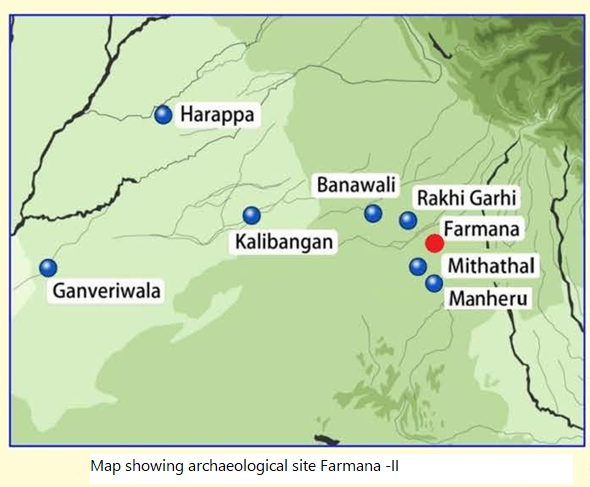

I see for the first time the word ‘Necropolis’ used for an archaeological excavation site of Indus valley civilization in one article written by Shinde. The report of the Indian archaeological society contains the article named ‘Harappan Necropolis at Farmana in the Ghaggar basin. Special report no.4 of the Indian archaeological society (2009). In this report, the authors have stated that at least part of the excavated site is a ‘Necropolis’. Unfortunately, the said report is not available anywhere on the net. (7) This report confirms my doubt that all these Indus excavation sites are burial grounds.

Evidence of earliest Cremation in Indus valley civilization

Indian Archaeologists are casually explaining some structures as ‘Pit dwelling’. Any decent living human being will not like to live in a pit, so this interpretation of Indian archaeologists needs to be appropriately tested.

Farmana Khas, or Daksh Khera, is an archaeological site in the Meham block of Rohtak district in the northern Indian state of Haryana, spread over 18.5 hectares. It is located near the village of Farmana Khas, about 15 kilometres from the Rohtak-Hissar highway and 60 kilometres from Delhi. It is significant mainly for its burial site, with 70 burials of the Mature Harappan period (2500–2000 B.C.) and relatively recent addition (excavation started in 2006) to Indus Valley Civilization sites excavated in India. (6)

Figure 3: Location map of Farmana. Picture courtesy (7)

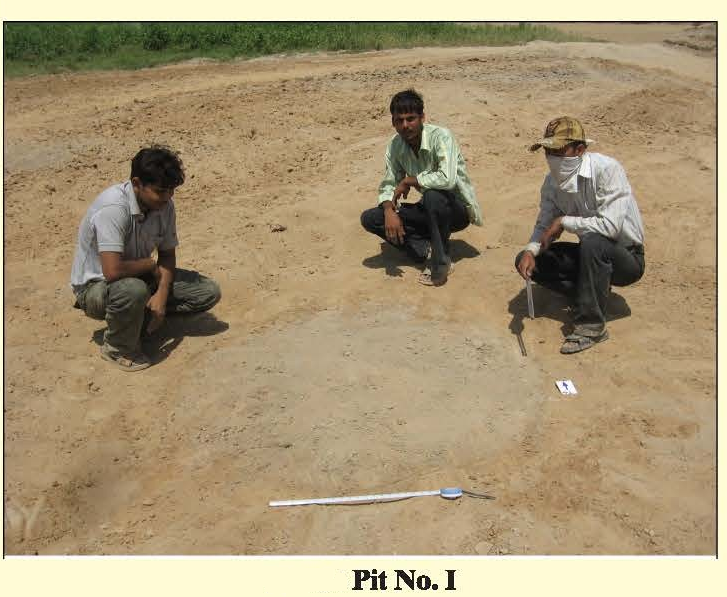

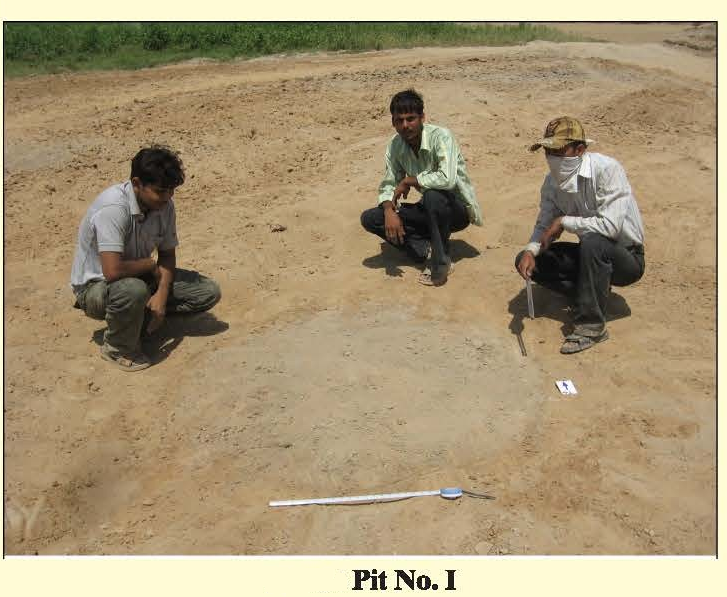

Narender Parmar reports that In Farmana-II, Haryana, the archaeologists have uncovered a ‘pit dwelling’ (7). Closure scrutiny of the photo shows that it is not the case of a ‘pit dwelling’.

Figure 4: Discoloured soil in a circle of 5 feet in diameter. Picture courtesy (7)

See the above-given figure -4; the circle is hardly 5 feet in diameter; nobody could have lived in such a small pit dwelling. Narender reports that a layer of ash, charcoal and bones was found in this pit. There is a possibility that it was a sacrificial pit, where one thigh of an animal (Leg piece of sacrificed Bull) would be burnt as a burnt offering to gods. The remains of the bone could be that of a sacrificed animal. Otherwise, the second possibility is that it could be a funeral pyre, and the bones could be the burnt remains of a dead body. Proper analysis of ash residue and bone remnants will yield a good result.

The picture shows circular discolouration, not clear-cut evidence of ‘Pit-Dwelling’. Only burning of the dead body requires 5 feet diameter fire circle. Since this fire circle has been found on a burial mound, it should be assumed that it is the fire of a funeral pyre. My conclusion is that it is the remnant of a funeral fire. It is the earliest recorded evidence of cremation in the Indus valley civilization.

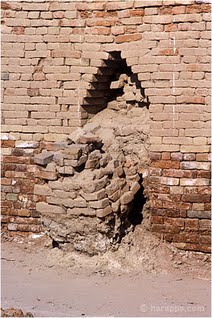

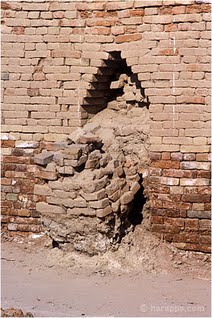

Figure 5: Entrance of a tomb. Picture courtesy Harappa.com

Drainage system

Much is being said about the drainage system of the two cities. Experts dealing with these sites undoubtedly believed that sustaining such a vast population could be possible because it had such a proper drainage system. A closer look at the photographs presented in the website Harappa.com shows that the drainage is 6 feet high and it is elevated and broad enough to allow a person to walk through the passageway. (See also figure-18) Indian cities do not have more than four feet of drainage pipes, even today in modern times. What was the necessity to build such a passageway? No doubt, they were passageways, not for cleaning the blocked drains, but they were passageways to enter the tombs, inner burial chambers, or burial rooms. These passageways would have been closed after placing mummified bodies inside the burial chambers. The closed passages are visible in the photos presented on Harappa.com. These closed passageways give a false impression that later-day occupants have blocked the drainage and built new houses.

We cannot correlate this passageway to the tomb’s entry passage because the burial chamber’s roof had fallen. The burial chambers would have been constructed like a room. High-quality timbers would probably not have supported the ceilings like in a typical living house. Even if high-quality wood had been used as rafters, those rafters would not have survived the ravages of time over thousands of years. Naturally, the ceilings had fallen over time. Passageways have withstood the onslaught of time because there is no wood usage in those cobbled arch pathways, but burial rooms have not survived. In this scenario, we cannot visualize that it could have been a tomb. Two essential pieces of evidence of these excavation sites are burial chambers and passageways, but these two facts have not been linked together. Interpreting only the passages has resulted in wrong conclusions.

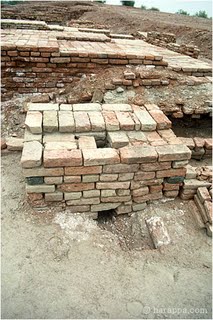

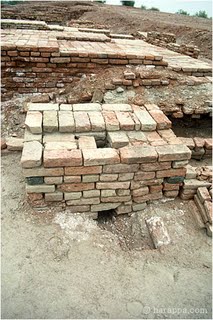

Figure 6: Dyer’s platform. Picture courtesy Harappa.com.

This enclosed hall shown in the illustration has been named dyer’s workshop. From the depiction, we can assume that huge pots would have been kept on those circular platforms, which created a depression in the middle. Some utensils with round bottoms were held on those platforms. Generally, flat-bottom metal vessels called “vats” are used for dyeing. Earthen pots with narrow mouths will not fit into the role of dying vats. Earthen pots cannot withstand the rigour of dyeing activity. In addition, the dying of clothes would have required a heating system for warming up the dying solution for proper adhesion to clothes, but no such heating facility is seen. If the purpose of these platforms is considered in light of the new theory, then the utility of the above-said platforms will perfectly fall into place. These platforms could have been used for keeping “Burial pots” (Funeral pots with a dead body inside),

Figure 7: Grinding mill platforms.Picture courtesy (8)

Platforms for grinding mills or burial pots?

Five to six round platforms are clustered in a narrow space near the granary. At present, these platforms are being described as platforms for grinding grains. The usage of the platform is still not explicit. If the above-said view that the rooms were burial chambers, then the use of the platform will also fall into place. The picture of the platform on Images of Asia.com shows three or four platforms in a single room. It looks like those platforms were built to keep the funeral burial pots over them; such a huge pot containing a mummified body would have required a stable platform.

What happened to the grinding millstones? If so many platforms are available, why are the grinding stones missing? The grinding stones are made of granite, and chances are more that the grinding stone should have survived than the brick platform. Bricks are fragile and should have been destroyed much before the grinding stones. Suppose so many platforms were used for grinding grains. In that case, Mohenjo Daro should have been an industrial centre with many grain-milling factories beating all other civilizations of that time. The new interpretation is that these platforms were used to keep funeral burial pots, not grinding mills.

The second possibility is that those round platforms could have been used for Vedic Yajna. At this juncture, it is relevant to note the syena citi found in Purola, Uttarkhand state. The ancient site at Purola is located on the left bank of river Kamal in District Uttarkashi. Hemwati Nandan Bahuguna University, Srinagar Garhwal, carried out the excavation. (9)

Figure 8: Huge Vedic altar in the shape of a Falcon.Picture courtesy (9)

The site yielded the remains of Painted Grey Ware (PGW) from the earliest level. Other materials include terracotta figurines, beads, potter-stamp, and a domesticated horse’s dental and femur portions (Equas Cabalus Linn). The most important finding from the site is a brick altar identified as Syena chitti by the excavator. The structure is shaped like a flying eagle Garuda, head facing east with outstretched wings and a square chamber in the middle. This chamber contained pottery remains assignable to circa the first century B.C. to the second century A.D. The findings also include a copper coin, bone pieces and a thin gold leaf impressed with a human figure identified as Agni. (9)

The Shulba Sutras are part of the larger corpus of texts called the Shrauta Sutras, considered appendices to the Vedas. They are the only sources of knowledge of Indian mathematics from the Vedic period. Unique fire-altar shapes were associated with special gifts from the Gods. For instance, “he who desires heaven is to construct a fire-altar in the form of a falcon”. Those who desire the world of Brahman should construct “a fire-altar in the form of a tortoise. “those who wish to destroy existing and future enemies should construct a fire-altar in the form of a rhombus”. (10) (11) (12)

Papers presented at the 12th world Sanskrit conference indicate the ‘Ratha wheel’ type altars were built. (13 p. 44). It was called ‘ratha-chakra-citi’. This kind of ratha chakra citi confirms a possibility of yajna conducted in a ‘wheel type’ Vedic altar. In addition, the picture shows (figure-7) four wheels in an adjacent area, like the four wheels of a ratha.

Based on the evidence provided by the massive structure built for syena citi, it can be assumed that there would have been different types of altars for various purposes. It looks like those circular platforms were some Yajna platforms used by the Harappan priests.

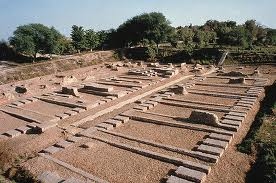

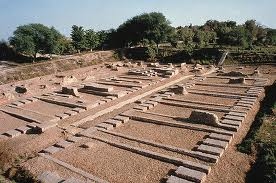

Figure 9: Granary. Picture courtesy Harappa.com.

Granary or Brick -kiln?

The structure identified as a granary is doubtful, as American history professor Kenoyer; suggests it could be merely a big hall. (14) Scrutiny of the photographs available onHarappa.com shows that it looks more like a brick kiln than a big hall. (15) Another possibility is that it could have been the kiln used for firing the massive number of funeral potteries used in those sites. Note that the bricks extracted from these two places were used as ballast for the considerable length of the railway line during the British period. Note that large numbers of bricks were used to construct these burial tombs. For such a large-scale consumption of bricks, they should have been manufactured on an industrial scale.

Mohenjo Daro and Harappa were important places of those times, and mortuary business was likely carried out on an industrial scale in these places in ancient times. The industry, which survived at these sites, was the funeral industry, and the business was mummification. Further, Kenoyer says that some ventilation pipe-like structure exists, leading to the conclusion that it was a granary. The ventilation arrangement is an essential module in a brick kiln for properly burning bricks. The granary depiction in various simulated models feels like a brick kiln rather than a granary. (14).

The second possibility is that these remnants could be that of a row of burial chambers built uniformly. Kenoyer says all these rooms were built in a single stroke, and this building has been rebuilt twice. That shows the importance attached to this building. Most probably, they were burial vaults of a noble family. It is a common practice in the Middle East and Egypt that burial vaults will be built in advance, even before the death of a person in a royal family. Additional chambers will be built along with that of Pharaoh for the female members and other family members. This structure could be that of serial burial chambers built uniformly.

The claim of the granary is doubtful. Storing grains on such a large scale is difficult. The grains had to be adequately dried, or they would rot within days of storage. Large-scale insect attacks will also occur in granaries. The control of rats will be next to the impossible task in such large-scale storage of grains. Based on all these factors, it can be safely concluded that the structure was not granary. In addition, there is another valid question, “Whether Indus people had any such huge surplus production of grains to store in such big granaries?” It is unlikely that the Indus people would have had enormous surplus production to store in such granaries.

This new theory of “necropolises” may give rise to doubt that there is no evidence for dead bodies being kept in burial pots. Even though burial in urns was standard practice in ancient times, that practice disappeared a long time back. Large numbers of medium-sized pots were excavated from these sites, which can be seen in the museums. Such medium pots will not accommodate an entire dead body. But, those medium-sized burial pots could accommodate the bones exhumed from low burial pits and re-interned, another standard practice for disposing of dead bodies in ancient times.

There is no evidence of preserved bodies at Indus sites because such preserved bodies would have crumbled on exposure to light. The grave robbers played a significant role in robbing these mortuary temples and destroying mummies. While extracting valuables from preserved bodies, the robbers would have exposed the mummies to the elements, which naturally destroyed those mummies within a few days or months. George Wunderlich gives a detailed account of this issue, why no such mummies have been found in the palace structure at Crete. (16) Arthur Evans had wrongly concluded the Minoan funeral complex was a “palace” because of the same reason that no mummies were found at the time of excavations. In this regard, the explanations given by George Wunderlich are informative and enlightening and apply to the situation in Indus excavation sites also. (16)

At this juncture, it is relevant to note that Vedas frequently mention that Indra burnt the ‘puras’ of dark-skinned people. Most probably, ‘Pura’ could have meant ‘necropolises’ of the Indus people. The Aryan god Indra could have burnt those necropolises because the fire was easy to destroy places like necropolises.

Figure 10: Well or shaft of a grave?

Well, or shaft of a grave?

The photograph of the well shows that the parapet wall starts from ground level and goes up to a two-storey level of the nearby building. See the figure-10 and compare the level of the well and adjacent wall (15). The well is not going down into the earth. And instead of that, it is growing up towards the sky. It was probably a shaft (passageway) to the inner burial chamber at a lower level, but it looks like a well.

Figure 11: Heart-shaped well?

Some wells are oval-shaped; some are heart-shaped (Photos of (15)). I am yet to see an oval-shaped parapet wall of well construction in any existing wells in India. See, the heart-shaped parapet wall has been built over a brick platform. The wall is hardly one foot in height, and there is no well below. Then, what is the purpose of this construction? It is merely a grave. A mourning man probably could have built this grave for his young dead wife, showing his love and affection by the heart shape.

Figure 12: Toilet?

Toilet or simply a hole in the grave?

The photo of the blocked drain presented on Harappa.com shows that it was merely an entrance to the tomb. It was unnecessary to build such massive sewers of man’s height during those ancient times. Even today, Indian metro cities only have two to four feet in diameter drainage pipes. In such a situation, building six feet high drainage channel is ill-logical and without any requirement for such a facility. Most probably, Harappans would have used open toilets in the backyards of their houses, as is the practice in rural India even today, not sophisticated toilets as imagined by some archaeologists.

Most of the open toilets of India used to be short walls (of one-foot height, one-foot breadth and three feet long) on which a person would squat, not a platform with a hole. Platform with a hole means the body parts will be touching the surface of the seat, which could be in a highly soiled and contaminated condition. Such a scenario is unthinkable, even in ancient times. Even if some toilet-like structure had been found, such facilities would most likely have been used to clean dead bodies and flush out internal remains during the mummification process. George Wunderlich explained “Cretan Palace toilets” in this way, which is applicable here in Indus sites.

Figure 13: Protruding pots.

Blood sacrifice pots

The potteries are also tailor-made for funeral purposes. Some show a protruding tube for funnelling the sacrificial blood into the ground. These protruding pots would have been filled with blood and then placed on the ground. The protrusion would have helped to keep the container straight on the funeral mound. Breaking the protruded portion would have allowed the blood to flow. The priest would have allowed the blood to drain away slowly. It would have given the impression that the souls of ancestors were drinking blood.

See the small hole in the middle pot shown in the above-given photo. That little hole would have allowed the seepage of blood into the ground. The “toilets” described by archaeologists seem to be “ordinary holes” meant for pouring blood into underground chambers to nourish the dead body in the underground burial chambers. (Or) Such protruded pots would have been kept in these “toilet holes” to allow the blood to seep away slowly.

Mortuary temples and Oracles

This blood-offering practice can best be understood by verifying the passage in the Greek classic book Odyssey. (17) In chapter XI, Homer narrates how Odysseus entered the underworld and consulted the soul of his dead mother. In addition, he sees the souls of other dead friends and learns about the happenings at Ithaca. Odysseus wanted to know about the future to decide the course of action. Ancient Indus culture could have contained similar ideas. The Harappan mortuary temples would have been like the underworld mentioned in Odyssey. Some oracles would likely have lived in those mortuary temples and acted as a medium to consult the dead people. Ancient Harappan worshipers would probably have visited these places to consult their ancestors through oracles.

Figure 14: Mound of broken pots. Picture courtesy (8)

Burial place and cremation ground

One of the photographs on the website Images of Asia shows an enormous amount of broken pottery. The broken pieces have been heaped into small mounds, and such a scenario is impossible in an ordinary site. A traditional explanation would be that it would have been a potter’s yard. If a potter produced and broke all his pots or produced such poor quality pots that a large number of pots broke at the manufacturing stage itself, then such a potter would not have survived for long. The probable explanation is that these sites at Mohenjo Daro and Harappa were necropolises, and ancient Hindus could have carried out their funeral ceremonies here for centuries. During such funeral services, many pots will be deliberately broken. That explains the large number of broken potteries seen in the photograph.

Many theories about the decline of IVC are also doubtful because it never declined in the real sense. Many of the cultural ideas depicted in Indus seals are still practised today. It looks as if Indus culture had declined because of the deserted nature of excavation sites. The sites would have looked deserted during excavation by British archaeologists because they were burial grounds and not residential places. A burial place will naturally give an abandoned look because of the fear of ghosts, and no one will occupy such a place.

In contrast, a residential place is valuable real estate and will never be deserted; it will be rebuilt generation after generation. Even if new invaders had captured these residential places, they would have occupied them after expelling the inhabitants of those sites. Those Indus sites were not rebuilt because they were haunted places, and no one wanted to live in such areas. The culture of building elaborate tomb houses vanished with the arrival of Indo-Europeans, who were tomb raiders, not tomb makers.

Bones and skeletons Ignored by Archaeologists

During excavations, some bones and skeletons were found. In addition to that, some fields have been marked as graveyards. A large number of bones collected have been dumped together in kept in storage boxes in the Archaeological Survey of India office at Calcutta. Proper stratigraphic recordings of the place of find and strata of the finding of bones were not done because the archaeologists never visualized that these sites could have been burial yards. A relevant question will be raised: why were no human bones found in the excavated area if these places were cemeteries?

Many skeletons and bones were not found in these sites to fit this new graveyard theory. Mummies or dead bodies were not found because later day invaders and grave robbers had destroyed these tombs and their mummies. When dead bodies and bones were exposed to light and heat, bones would have pulverized within a few days. Similar is the explanation offered by Wunderlich in his book for this same question.

During my visit to Dholavira, one of the vital points said by the guide was the presence of a large number of bone fragments in the soil. He merely scooped out the dirt and showed the presence of bone fragments. The presence of bones indicates that many human burials would have taken place at these sites. There is also the possibility of the large-scale sacrifice of animals to satisfy the ‘Pithrus’ (dead ancestors).

There is sufficient evidence of skeletons in these sites to support the necropolis theory. In Possehl’s book, the map on page 160 (Figure 9.1) shows that skeletons are strewn all over the place, not restricted to any small location as normally expected. (18) The random spread of skeletons all around indicates that the entire area was used as a burial ground and not merely a tiny enclosure within site.

Research work of Gwen Robbins

Gwen Robbins has done an excellent study on skeletons found at IVC sites and presented the paper without distortion. The research paper is a forensic examination of bones and skeletons found during Indus Valley excavations. The author presents the significant reasons for death among the skeletons found in IVC. A careful study of the research paper shows that death due to various diseases was also a significant cause of death other than violence.

If the Aryans had suddenly invaded those cities and killed those inhabitants, then the skeletons would have only been that of healthy individuals. Whereas the skeletons also include a high level of diseased people. Infectious diseases like leprosy and tuberculosis were the primary cause of death other than death due to trauma (due to violence). This shows that these IVC sites were burial yards, and all diseased people had been buried there. The only deficiency in this research paper is that the author is unaware that those IVC sites were burial yards. She has merely correlated her findings with already existing theories on IVC decline. (19)

Research work of Brad Chase

Brad Chase has worked on the excavation site at Gola Dhoro in Gujarat state, India and presented his paper on animal bones found at that site. The work reveals the presence of a large number of animal bones inside the citadel and outside the citadel. He concludes that the standard dietary patterns of the people of Gola Dhoro included beef, mutton and tortoises. The bones found at this site indicated the killing of many cattle. He concludes that the food preferences of people inside and outside the citadel differed. Further, he observes that earlier occupants’ food preferences changed from later ones.

All these interpretations are shallow. Finding a large number of animal bones shows that animal sacrifices were carried out inside the citadel as well as the outside castle. The tombs of notable people were likely located inside the fortification, and the graves of ordinary people were outside the fortress. The data shows no significant difference in finding bones of cattle and goats between outside areas of the citadel and inside of the citadel. Again the problem with this research paper is that even though the data is collected and presented meticulously. The conclusions are far from satisfactory. The deficiency is that the author is unaware of the nature of killing these animals. His conclusion would have been much more conclusive if he had been aware those animals were sacrificed in a cemetery. If the data provided by Brad chase is analyzed from this perspective of the graveyard and animal sacrifice, there would be much more fruitful conclusions on this subject. (20)

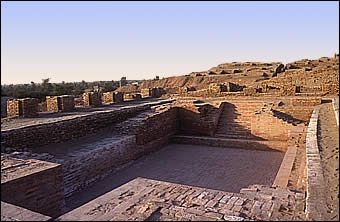

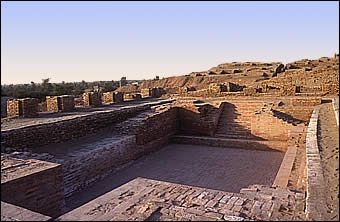

Figure 15: Great Bath.

A new interpretation of “Great Bath”.

Close observation of the great bath shows that this structure is entirely made of bricks, and no stone is used. No stones are used in the footsteps also. This soft construction material indicates that this structure was not used daily. Please pay attention to any water tank in India; all of them have stone side walls and stone footsteps because when you use these steps daily, there will be a lot of wear and tear, and such kinds of brick steps will not suffice. Further, if the water tank is constructed with brick side walls, the bricks will allow the water to seep away, and the brick will turn into dust in a few years. These observations show that this Great Bath structure was not used for regular bathing and could have been used as a courtyard for other ceremonies.

This Great Bath could have been used for a ritual bath is doubtful because filling water in such a big water tank could have been a difficult task. The second point against the idea of filling the tank with water is that it will be almost impossible to fill it with manual labour. Whatever water you pour into this tank will disappear in a few hours. Only a modern, high-duty, high-volume centrifugal pump could fill such a tank.

This idea of the cemetery is supported by the finding of Hans George Wunderlich, described in his book, “Secret of Crete“. (16) While contemplating the mortuary palaces at Knossos at Crete, he concluded that the steps used in those mortuary palaces were made of “White Soft Calcite stones”(Alabaster) (Soft -Soap stones) which would not withstand the rigour of daily usage. Marble stones used in the Taj Mahal are harder stones that could resist the severity of regular usage. George Wunderlist was a geology professor. His knowledge about the quality of rocks was fundamental to his new theory that those Cretan palaces were “Mortuary Palaces” and not “regular palaces” meant for living. This concept is very much applicable to “Indus- Great Bath”.

Based on the conclusions of Wunderlich, his assumptions can be safely applied to this “great bath” of the Indus Valley civilization. It appears that this structure was a kind of inner courtyard of a building. Because later day construction over and above the level of this inner courtyard looks like a “water pool”. Remember that these sites have seven strata (layers) of construction. Probably the inner courtyard could have been used for the sacrifice of animals.

Later, that particular funeral hall would have fallen out of use after many generations. Then, an entirely new family set could have occupied and re-used that specific patch of the cemetery as their burial yard. In that process, they could have filled up the old structure and built a new layer of funeral and anti-chambers for animal sacrifice. The conclusion is that “The Great Bath” was simply an inner courtyard used for animal sacrifice ceremonies and not as a “bathing tank”.

The inner courtyard shows the stone pillars (stakes) in which sacrificial animals were tied. Picture courtesy (21)

Notably, the Dholavira has a similar courtyard with sacrificial stakes, which had been appropriately explained as a sacrificial yard. But the same sacrificial enclosure becomes a swimming pool in Mohejo Daro. What a pathetic explanation! And inadequate reconciliation of facts.

Mortuary temple and Mummification source of money

Mummification would likely have been carried out in these Indus sites. Mummification would have brought in a lot of revenue for those professional physicians and funeral priests. Further, as long as mummies existed, those mummies would have required regular poojas and animal sacrifices supposedly to sustain the souls of those dead persons. All these activities would have sustained the mortuary temples of these places. Even though there is no evidence of mummification in Hindu culture today, the remnants of that practice can be seen in present-day rituals for the dead.

After the body’s cremation, the final ceremony is held only on the 40th day; until then, the mourning period continues. How is this period of 40 days of mourning arrived at? It is merely because the mummification process required 40 days to preserve a body properly. Verifying the data available with Egyptian mummification techniques would show that it took 40 days to preserve the body. Further, it should be noted that IVC people had burial practices, but later, steppe people had cremation as a standard practice. Because of that, the burial customs have vanished in the long run.

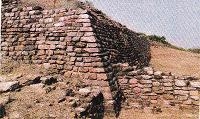

Figure 16: Slanting walls of the citadel, Dholavira.Picture courtesy (22)

Figure 17: Slanting walls of Mastaba. Picture courtesy Wikipedia

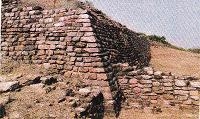

Dholavira: Citadel or Mastaba

R.S. Bisht, the archaeologist who excavated this Dholavira site, states the presence of a citadel in the centre of the excavation site. The walls shown in the above picture are considered as remnants of a citadel. But, if you see the image of a citadel wall, it can be seen as a slanting wall, not a perpendicular one. How will the fortification wall be slanting in nature? The walls of a fort are always vertical and perpendicular to the ground. If you have a sloping wall in the fort, the enemy will climb the walls very quickly, and the entire purpose of the fort will be defeated. But, the reality is that the walls of Dholavira are slanting, and it cannot be a citadel. Consider the walls of Mastaba shown in the picture on the right side; the walls are sloping at a 30-degree angle and exactly match the photo of the Dholavira citadel wall shown in the figure. The only explanation for the structure in Dholavira is that it is a Mastaba. (23) (Note-3)

Other supporting evidence for Mastaba Theory:

●Entrances to this citadel are not aligned in a straight line and are in different alignments, more like a labyrinth than a citadel.

●The enclosed area of this citadel is minimal; the fort requires a large area for people living within the fort.

●There are only water tanks, but no proper living quarters are identified within the fort.

●There is no citadel-like structure –courtroom, living room, the dining room of royalty or nobles.

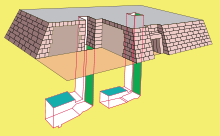

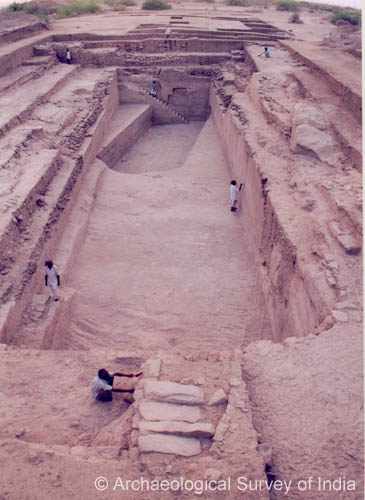

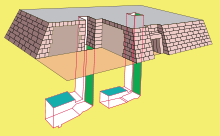

Figure 18: Tunnel of Dholavira. Picture courtesy –ASI website –link-4 (24)

Tunnel and water tanks of Dholavira:

Now, let us analyze the tunnel of Dholavira more professionally. A full-grown man can easily walk through this tunnel. What is the standard explanation for this tunnel? A tunnel for rainwater collecting, water passes through the tunnel to enter the massive water tanks located within the excavated site. Fortunately, the site’s excavator has given a new purpose to this tunnel instead of the old explanation that the tunnels were meant for a sewage drainage system. In that way, it is a positive development, and this explanation indirectly supports my theory that the description of the “Drainage system of IVC sites is wrong”. (23)

Six or seven large water tanks surround the core citadel area. The simple logic is enough to refute this theory; water will run by gravitational force to reach the big water tanks at a lower elevation than the citadel. There is no need for extensive tunnels to harvest rainwater. My explanation is that it is a “passage tunnel” to a “burial chamber“. (23)

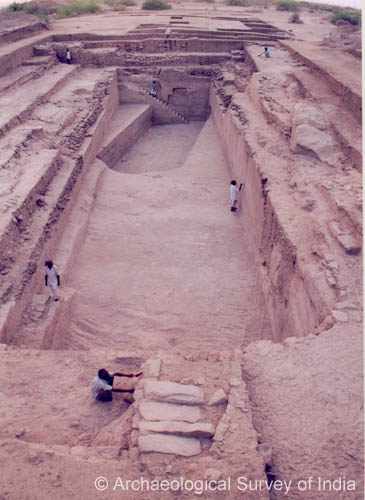

Figure 19: Water tank of Dholavira.

The above-given photo shows a chamber, which the guide could not explain. The standard explanation is that it could be another water tank. It could not be a water tank because there is no water chute leading to this chamber, and other surrounding water tanks are lower than this chamber. Further, the walls of this chamber are porous and not watertight. In addition to this chamber, there exists another chamber side by side of the same proportion. A division of two feet of thickness separates both chambers. If the chamber had been built for water collection, there would be no logic in building a separating wall into two water tanks. (23)

A possible explanation is that it could be a burial chamber. Dholavira is an exciting place from the archaeologist’s point of view because the site has been only partially explored. Further excavations could lead to burial chambers and possible new artefacts. (23)

Other supporting evidence for the “Necropolis theory” in the Dholavira excavation site

A)There are many burial pits and chambers on the southern side of the supposed to be the citadel.

Figure 20: ‘A burial’ as per narration of ASI (Picture courtesy- ASI –website-link-1 (25)

Figure 21: A burial with limestone lining all around, along with burial pots. ASI website –link-2 (26)

B) As explained above, six or seven water tanks surround the citadel, which could be large burial chambers instead of water tanks.

Figure 22(ASI website, link-3)Picture courtesy (27)

C) The tunnels, as shown above (Figure-18), could be passageways leading to “Dungeons” if there had been any ruling elite in this place in ancient times. But, the site’s excavators are afraid of proposing such an explanation. Hence, the assumption of an “entrance tunnel” to a burial chamber is a reasonable explanation. (ASI, Link-4)

D) There is a massive well in the centre of the citadel, which could be the “shaft grave”, similar to the shaft grave found in Greece. See notes Nos. 1&2 at the bottom of the article, describing shaft graves’ nature, character, and functions. If this shaft grave is further excavated, there may be a chance of finding a burial chamber.

Figure 23: Well, within the citadel, Dholavira. Photo courtesy (28)

Even if the burial chamber had been plundered in ancient times, there would be evidence of a burial chamber at the bottom of this well. It was standard practice in Egypt to have a big shaft tunnel, and burial chambers would be cut into the rock layers at the bottom of the pit. Cutting the burial chambers into the rocky layer is the ultimate protection for the everlasting survival of burial chambers. The same thing was done in Dholavira also. However, people are identifying such tunnels as wells.

Arguments against “Well Theory”:

● Please note that a small cist grave exists next to the well; it is unusual to have a cemetery next to a drinking water well.

●The only supporting evidence for “well theory” is the existence of a platform and a pulley, and other structures to pull out water from the well. (Figure -23: photo of ASI)

● This “well theory” could be easily refuted. Any underground burial chambers could have required a pulley and lift mechanism for downloading construction materials and mummified bodies.

●This “shaft graves” method was developed to prevent easy accessibility to grave robbers. In addition, mummified bodies could be accessed for prayers, and periodic maintenance of burial chambers could be carried out. At the same time, ancient people could build additional rooms inside the shafts for the other dead family members of royal or noble families.

E) There is a grave chamber located very near the well. The cist grave is the small square pit in the middle of the chamber. Most probably, the “capstone” of the “cist” has been removed. Because of that, it gives an appearance of a pit inside the larger crater. (Figure -24)

Figure 24: A pushkarini in the castle as per ASI. (Photo courtesy (29)

However, ASI calls it Pushkarini (Stepped Tank) (figure 24). Compare the figures given in 20&24; both are similar structures. However, archaeologists call the structure in figure 20 a burial chamber and the structure in figure -24 as pushkarini. What a contradiction!

Arguments against the “Stepped Tank” Theory:

●This pushkarini is just next to the deep well. If a deep well is nearby, how will water stay in a shallow tank near a well?

●Is there any logic in building a shallow pushkarini beside a deep well?

●Those seven are eight big water tanks located in the citadel area, where this pushkarini is situated. This pushkarini is very small compared to the massive water tanks.

●Those massive water tanks are located at a lower elevation than this pushkarini, so the outcome will be that no water will stay in this pushkarini even in the rainy season.

●The conclusion is that it is not a pushkarini but could be a cist grave or pit grave.

F) Existence of a peephole on the false door in Dholavira: There will be a provision for a false door in Egyptian pyramids and Mastabas. The Ancient Egyptians believed that the false door was a threshold between the living and the dead worlds. Through the false door, a deity or the deceased’s spirit could enter and exit. (Figure-25)

Figure 25: False door in a pyramid.Picture courtesy Wikipedia (30)

The false door was usually the focus of a tomb’s offering chapel, where family members could place offerings for the deceased on a unique offering slab in front of the door. (30).

Figure 26: View of Pharaoh’s statue through the peephole. Picture courtesy (31)

The serdab chamber has a small slit or hole to allow the deceased’s soul to move freely. These holes also let in the smells of the offerings presented to the statue. (31)

Figure 27: The photo shows the peephole to the inner chamber. Dholavira. Picture courtesy – Sameer Panchal, Mumbai.

A similar slit-like structure exists in one of the chamber walls of Dholavira. The above-given picture shows the peeping hole, and the guide could not explain the role of a small window-like opening on the wall. We cannot visualize the inner room because the roof of the place had caved in and filled with mud. It just gives the appearance of a small window-like structure.

Figure 28: Eye of the underworld. Picture courtesy (32)

The slit-like structure available in the net is reproduced here above (Figure-28) for information’s sake. This picture shows the eye of the underworld found in Sumer (32). This narrow slit opening is for the ‘Ba’ (soul of the dead person) to move in and out of the burial chamber. That is what ancient Egyptians believed, and the ancient Indians also thought the same way.

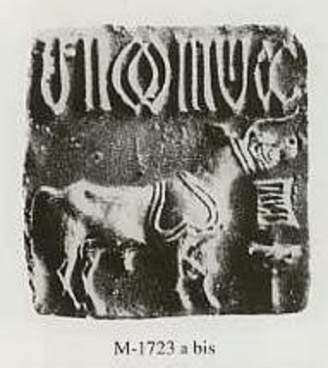

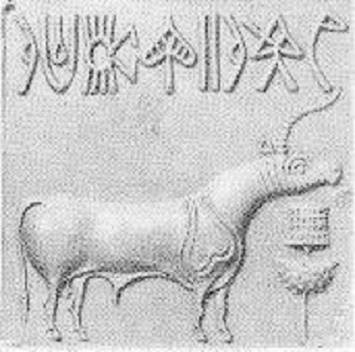

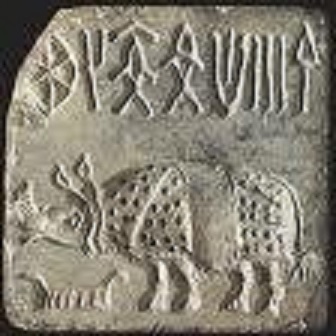

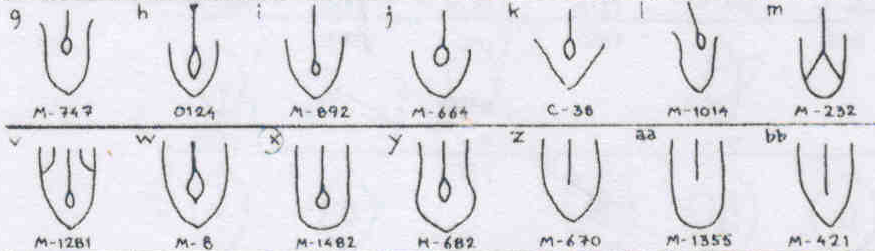

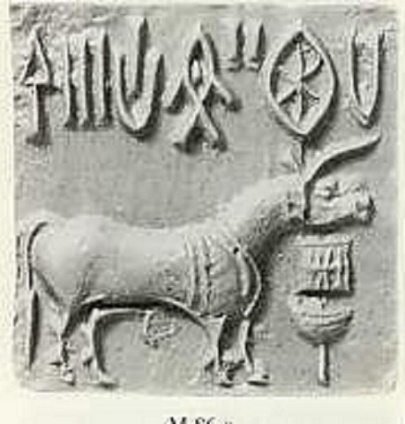

Decipherment of Indus seals

The current explanation is that the seals were used as some token of the identity of ownership of goods exchanged in trade, and this explanation does not seem to be correct. Analysis of Indus inscriptions on seals reveals that these inscriptions describe the Pithru karma ceremony and specific gods to whom the sacrifice was made. Sometimes sacrifice was made to please the gatekeeper god. (33) Majority of the time, the slaughter was done to please the god ‘Rudra’. This issue is being separately discussed in another article under ‘Rudra was the most important god of IVC ‘. (34)

Decipherment of Indus inscriptions shows that animals were sacrificed in Indus Valley Civilization. This finding indicates a correlation between “Necropolis theory” and “Indus seals “. Thus, the “Inscriptions on Indus seals” substantially supports the “Necropolis theory”.

The decline of the Indus civilization

So many theories have been propounded to explain the decline of Indus culture, but none is satisfactory because it never declined in the real sense. Imagine that Indus people were using those places as necropolises, and later came the invaders with scant respect for those buried there. Those invaders could have destroyed those places because their main intention was to dig out valuable items like gold jewellery, utensils, or weapons buried with the deceased.

Later entirely new culture came; they were the people who burnt the body to outsmart the grave robbers. In the latter-day, Eurasian steppe people followed cremation practices. This cremation became a more prominent practice in India, and the old burial tradition declined, resulting in the burning of all funeral materials. It is not only that to avoid grave robbery but also to prevent magicians’ use of body parts. Black magic” requires the body parts of deceased persons. The magician will make a “magic potion” out of body parts, and the Magician will control the dead person’s soul. That is a recurring theme in all the paranormal stories of India. Practically also black magic is still being practised in India even today. The later entrants to Indus Valley would have preferred to burn the dead body to avoid such a fate to the soul, ending in the hands of magicians.

These above-said problems could have resulted in the shift in funeral practice in Indus Culture. The burning of bodies resulted in the absence of grave goods; this resulted in a scene where it gives an impression that cultureless people occupied these places. Cultured people were very much there, and Indus culture never declined in a proper sense, which explains the re-emergence of all cultural ideas of Indus people in the later period.

A similar situation existed in the Greek culture after the fall of Minoan palace culture. Ancient Greek history also contains a dark period in which no evidence of culture is seen. Later, it re-emerges after 500 years. Wunderlich correctly observes that it is wrong to conclude that no cultured people existed during that period. The only mistake of those people was that they were practising the burning of corpses instead of burial. The situation narrated by Wunderlich on Greek culture is very similar to the scenario presented in the Indus valley. (16)

At this stage, it is crucial to introduce the research work of David Reich, a Harvard professor. His genetic study has shown that the underlying substratum of the Indus population was of African origin mixed with Iranian farmers from Zagros mountain who reached India by 4000 BC. (35 p. 138) Later, Aryans arrived from southern Ukraine around 2000 B.C. (35) (36) This study is significant, and all books on the ancient history of the world and India had to be rewritten.

The above-given research work by David Reich conclusively proves the Aryan invasion theory and confirms the violent nature of Aryan tribes. It looks like the invading Aryans brought the practice of burning dead bodies and could have destroyed the burial chambers of the earlier civilization. Frequent mention of Indra burning ‘Puras’ also confirms the idea of destruction by invading Aryans.

Justification for cremation

The incoming of new people into the Indus valley changed the ancient ways of disposal of dead bodies. The newcomers did not respect old ways of living, especially Central Asian people, who used to cremate their dead. They followed cremation practices because they were nomads and could not protect their burial sites. Their enemies used to open graves and desecrate the bodies. So, the best way of disposal was to burn.

In contrast, IVC people were settled agriculturists; they were not moving anywhere and could protect their burial mounds for a long time. Once the nomads from the steppe entered India, they never had any respect for old burial sites. Ancient people used to bury the dead with their gold ornaments and other personal utensils. The latter-day nomads used to burn and destroy burial sites for gold.

These burial sites were considered entry points into the underworld of dead people. (17) Most probably, these entry points to underworlds were called ‘Purs‘ by the Indus valley people. ‘Pur’ means ‘hole’ in ancient Dravidian language, which means entry tunnel into the underworld. Hence these ‘Puras‘ (As mentioned in Vedas) became the target of all invaders and local grave robbers. Rig Veda frequently says that Indra destroyed the ‘Puras’. In Mesopotamia, such underworlds were called ‘Kur’; this word probably led to the formation of the name ‘Kurgan’ in central steppes. “Kurgan’ means the burial mound in the steppe language.

These Necropolises became unpopular because of the above-said reasons. Practically, the nomadic way of burning was cheap and practical. Further, the expenses on funeral ceremonies were reduced. Yearly rituals reduced. The latter-day Greek invaders also followed the cremation practice of burning the dead. Practically, the practice of burial of dead people disappeared from India.

Only graveyards and no towns or villages?

I doubt the existence of cities in IVC. But definitely, towns and villages would have existed. Many present-day towns and cities of India are developed over the old Harappan settlements. My observation is that the residential area of the villages would have been built many times over the millenniums. But, the nearby graveyards have been untouched for thousands of years. The villagers use the cemeteries but do not disturb them because they fear ghosts. We can retrieve part of our ancient history thanks to ghosts and spirits.

Indus towns would have been much more beautiful, elaborate and well planned

I am not saying there were no villages and towns in the Indus Valley civilization. My explanation of ‘Necropolis’ is restricted to the excavated sites at Mohenjo Daro and Harappa and other similar excavated sites. The ancient towns near Mohenjo Daro and Harappa necropolises would not have disappeared. They must still exist as bigger towns, as explained in the case of the village of Farmana. (37) You should think logically in a positive way. If the IVC people had given so much importance to the graveyard (burial place), what would have been the quality of their residential areas? The residential areas would have been much more elaborate and well-planned.

Mortuary temples-oracles -traders selling fancy items

The earliest archaeologists reported that the Brahmanabad (the old name of Mohenjo Daro) was an enormous ruin extending for many miles. Similar was the situation for Harappa also. These places would have been places of mortuary temples, professional embalmers and Oracle priests. Those embalmers and their assistants would have lived in nearby villages. Dead bodies would be brought from distant places for professional mummification and burial in the special chambers in Mohenjo Daro and Harappa for preservation. The religious idea of the Indus valley people was like the modern-day idea of ‘cryogenic preservation and possible resurrection on a later day.

Later, the relatives will visit the burial chambers to consult their dead relatives. The oracle priests would consult the dead ancestors and suggest a future course of action for the living people. That kind of religion, ancestor worship and consulting the dead, existed in ancient times. Such sort of faith was widespread all over the Mediterranean Sea littoral states. Please read the chapter in the book of Ulysses where he enters the underworld to consult his dead mother to get an excellent idea about this religious idea. (17)

A similar situation would have existed at Mohenjo Daro. People might not have lived in large numbers in such mummifying areas because such areas will be highly infectious. However, such places would have generated enough revenue to sustain Oracle priests, embalmers and traders selling trinkets, jewellery, bangles and other items. That is why archaeologists find hoards of gemstones, lapis lazuli and shells in the process of making them into bangles. Archaeologists immediately concluded that those sites were involved in the export of Lapis lazuli to other countries. The first possibility is that those semi-precious stones would be for local consumption. Traders selling Agarbathi (Incense Sticks), frankincense, and flowers would have had shops around these mortuary temples. In modern Hindu temples, shops selling pooja and fancy items still exist. This religious and cultural practice explains the presence of various factories around these excavation sites.

Note-1: Shaft graves, late Bronze Age (c. 1600–1450 BC)

Shaft graves were burial sites from the era in which the Greek mainland came under the cultural influence of Crete. The graves were those of royal or leading Greek families and remained unplundered and undisturbed until found by modern archaeologists at Mycenae. The graves, consisting of deep, rectangular shafts above stone-walled burial chambers, lie in two circles, one excavated in 1876 and the other not found until 1951. They were richly ornamented with gold and silver; carvings of chariots provided the earliest indication of chariots on the Greek mainland. (38)

Figure 29: Model of shaft grave.

Note-2: Shaft grave:

Definition: At Mycenae, wealthy warrior chieftains and their families were buried in shaft graves, such as in “Grave Circles A and B” (walled enclosures) from the Middle or Late Helladic period. A shaft grave is a large cistern-like structure entered through a roof’s opening. After the burial, the shaft is filled in with dirt. On the top, some had sepulchral stones. J.B. Bury says women wearing gold diadems with household items beside them were also buried in these graves. (39)

Note-3: This note is the extract of the article on Mastaba at Wikipedia

The word Mastaba comes from the Arabic word for a bench of mud, likely because it resembles a bench seen from a distance. It is also speculated that the Egyptians may have borrowed ideas from Mesopotamia because, at that time, both cultures were building similar structures. (40)

The above-ground structure was rectangular, and it had sloping sides, a flat roof, was about four times as long as it was wide, and rose to at least 30 feet in height. The Mastaba was built with a north-south orientation which was essential for Egyptians so that they may be able to access the afterlife. This above-ground structure had space for a small offering chapel equipped with a false door to which priests and family members brought food and other offerings for the soul (Ba) of the deceased. Because Egyptians believed that the soul had to be maintained to continue to exist in the afterlife, these openings “were not meant for viewing the statue but rather for allowing the fragrance of burning incense, and possibly the spells spoken in rituals, to reach the statue.” (40)

Inside the Mastaba, a deep chamber was dug into the ground and lined with stone or bricks. The burial chambers were cut deeper until they passed the bedrock and were lined with wood. The exterior building materials were bricks made of sun-dried mud, readily available from the Nile River. Even as more durable stone materials came into use, the cheaper and readily available mud bricks were used for all but the most important monumental structures.

A second hidden chamber called a “serdab”, from the Persian word for “cellar”. This chamber was used to store anything that may have been considered essential, such as beer, cereal, grain, clothes, and other precious items needed in the afterlife. The Mastaba housed a statue of the deceased hidden within the masonry for its protection. High up the walls of the serdab were small openings because, according to the ancient Egyptians, the Ba could leave the body, but it had to return to its body, or it would die. (40)

1. Leshnik, Lawrence.S. The Harappan port at Lothal:Another view. http://www.jstor.org/stable. [Online] 2015. http://www.jstor.org/stable/669756?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents.

2. wikipedia(Bhirrana). Bhirrana. wikipedia. [Online] 2015. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bhirrana.

3. Parmar, Narendar. Origin , developement and decline of first Urbanization in Upper Saraswati basin. academia.edu. [Online] 2015. https://www.academia.edu/s/e1b0330223#comment_57545.

4. google.co.in/maps. google.co.in/maps. https://www.google.co.in/maps. [Online] 2015. https://www.google.co.in/maps/@9.5946258,76.5205927,13z?hl=en.

5. Vasant Shinde, et al. Basic issues in Harappan Archaeology: some thoughts. http://www.ancient-asia-journal.com. [Online] 2015. http://www.ancient-asia-journal.com/articles/10.5334/aa.06107/.

6. wikipedia(Farmana). Farmana. wikipedia. [Online] 2015. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Farmana.

7. Parmar(Farmana), Narender. Recent_Discovery_of_the_Pit_Dwelling_complxes_from Farmana. https://www.academia.edu. [Online] january 2015. https://www.academia.edu/8373036/Recent_Discovery_of_the_Pit_Dwelling_complxes_from_Farmana-II_District_Rohtak_Haryana._Itihas_Darpan_18_2_213-222.

8. imagesofasia.com. mohenjodaro. www.imagesofasia.com. [Online] 2014. http://www.imagesofasia.com/html/mohenjodaro/.

9. ASI dehraduncircle. asidehraduncircle.in/excavation. https://www.asidehraduncircle.in/excavation.html. [Online] https://www.asidehraduncircle.in/excavation.html.

10. Wikipedia(Shulbasutra). Shulba_Sutras. wikipedia.org. [Online] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shulba_Sutras.

11. Sen, S.N. and Bag, A.K. The Śulba Sūtras of Baudhāyana, Āpastamba, Kātyāyana and Mānava with Text, English Translation and Commentary. . New Delhi : Indian national science academy, 1983.

12. Plofker, Kim. “Mathematics in India”. In Katz, Victor J (ed.). The Mathematics of Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, India, and Islam: A Sourcebook. . s.l. : Plofker, Kim (2007). “Mathematics in India”. In Katz, Victor J (ed.). The Mathematics of Princeton University Press. , 2007. ISBN 978-0-691-11485-9.

13. Wujastyk, Dominik. Mathematics and Medicine in Sanskrit. New Delhi : Motilal Banarasidas., 2008. Papers of the 12th world Sanskrit conference. Volume -7.

14. wikipedia(IVC). Indus_Valley_Civilization. wikipedia.org. [Online] 2015. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civilization.

15. Harappa.com. http://www.harappa.com/. http://www.harappa.com/. [Online] 2014. http://www.harappa.com/.

16. Wunderlich, H.G. The secret of crete. . Glascow : Macmillon Publishing Co.Ltd, 1974.

17. Homer. odyssey. classics.mit.edu. [Online] 2014. http://classics.mit.edu/Homer/odyssey.11.xi.html.

18. Possehl.L. The Indus Civilization. A contemporary perspective. New Delhi: Vistaar Publications. New Delhi : Vistaar Publications, 2003.

19. Robbins, Gwen. Bioarchaeology of Harappa. anthro.appstate.edu. [Online] 2014. http://anthro.appstate.edu/node/289.

20. Chase, Brad. beef-indus-valley-civilisation-1.pdf. http://beef.sabhlokcity.com. [Online] 2014. http://beef.sabhlokcity.com/Documents/beef-indus-valley-civilisation-1.pdf.

21. youtube.com. Dholavira. www.youtube.com/. [Online] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OypRduqmLZE.

22. Subramanian.T.S. The Harappan hub (Dholavira). Frontline. 12 July 2013.

23. Jeyakumar(Dholavira). dholovera—photos. sites.google.com/site/induscivilizationsite. [Online] 2014. https://sites.google.com/site/induscivilizationsite/home/dholovera—photos.

24. ASI(link-4). images/exec_dholavira. http://asi.nic.in. [Online] 2014. http://asi.nic.in/images/exec_dholavira/pages/026.html.

25. ASI(link1). /images/exec_dholavira. http://asi.nic.in/. [Online] 2014. http://asi.nic.in/images/exec_dholavira/pages/032.html.

26. ASI(Link-2). images/exec_dholavira. http://asi.nic.in. [Online] 2014. http://asi.nic.in/images/exec_dholavira/pages/031.html.

27. ASI(link-3). mages/exec_dholavira. http://asi.nic.in. [Online] 2014. http://asi.nic.in/images/exec_dholavira/pages/015.html.

28. ASI(link-6). images/exec_dholavira. http://asi.nic.in. [Online] 2014. http://asi.nic.in/images/exec_dholavira/pages/025.html.

29. ASI(link-5). http://asi.nic.in/images/exec_dholavira/pages/024.html. http://asi.nic.in/images/exec_dholavira/pages/024.html. [Online] 2014. http://asi.nic.in/images/exec_dholavira/pages/024.html.

30. wikipedia(False_door). False_door. http://en.wikipedia.org. [Online] 2015. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/False_door.

31. wikipedia(Serdab). Serdab. http://en.wikipedia.org. [Online] 2015. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Serdab.

32. Inanna. Inanna’s shrine. http://inannashrine.blogspot.in. [Online] 2015. http://inannashrine.blogspot.in/2007_02_01_archive.html.

33. jeyakumar(Gate-keeper-god). Karuppa_Swami_was_the_gate_keeper_god. academia.edu. [Online] 2015. https://www.academia.edu/10950376/Karuppa_Swami_was_the_gate_keeper_god.

34. Jeyakumar(Rudra). Rudra was the most important god of Indus Valley Civilization. www.academia.edu. [Online] https://www.academia.edu/43654003/Rudra_was_the_most_important_god_of_Indus_Valley_Civilization.

35. Reich, David. Who we are and how we got here. New York : Pantheon books, 2018. 9781101870327.

36. Joseph, Tony. Early Indians. New Delhi : Juggernaut Books, 2018. 9789386228987.

37. Jeyakumar(Farmana). Mystery_mounds_of_Indus_Valley_Civilization. https://www.academia.edu. [Online] june 2015. https://www.academia.edu/12489879/Mystery_mounds_of_Indus_Valley_Civilization.

38. Encyclopedia Britannica. shaft-graves. http://www.britannica.com. [Online] 2015. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/537605/shaft-graves.

39. ancienthistory.about.com. ShaftGraves. http://ancienthistory.about.com. [Online] 2014. http://ancienthistory.about.com/od/greekdeath/g/ShaftGraves.htm.

40. wikipedia(Mastaba). Mastaba. http://en.wikipedia.org. [Online] 2014. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mastaba.

-this symbol pair is occurring maximum times, that is 104 times. Yet these two symbols pair is not yielding any single meaning. Both symbols have to be read as separate entities. Number three indicates the ‘third day’ after death. whereas the tilak symbol indicates the word ‘karma’. It looks like that the intention of the priest, who made this inscription is not this combination. It is likely that the focal point of the priest was the word ‘Pithru Karma’ not ‘Karma-third day’.

-this symbol pair is occurring maximum times, that is 104 times. Yet these two symbols pair is not yielding any single meaning. Both symbols have to be read as separate entities. Number three indicates the ‘third day’ after death. whereas the tilak symbol indicates the word ‘karma’. It looks like that the intention of the priest, who made this inscription is not this combination. It is likely that the focal point of the priest was the word ‘Pithru Karma’ not ‘Karma-third day’. fish -karma symbol makes sense. The fish symbol stands for Pithru. Three different kinds of fishes indicate the three generations of Pithrus.

fish -karma symbol makes sense. The fish symbol stands for Pithru. Three different kinds of fishes indicate the three generations of Pithrus. it should be read as ‘Pithru Karma’. Then the frequency of this

it should be read as ‘Pithru Karma’. Then the frequency of this  combination of symbols increases. Total frequency of this combination stands at 75. This frequency is definitely significant for sample size under consideration.

combination of symbols increases. Total frequency of this combination stands at 75. This frequency is definitely significant for sample size under consideration. pair of symbols. Sometimes this tilak symbol ‘

pair of symbols. Sometimes this tilak symbol ‘

– Yajna

– Yajna